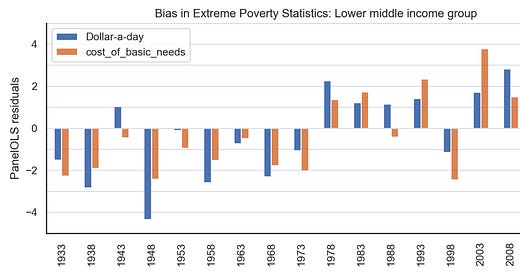

I was alerted to the fraud by Tom Stevenson, a very sharp knife who usually writes for the London Review of Books. For him, the dramatic reduction in extreme poverty hailed by the World Bank—and taken seriously by many serious people, including myself until he alerted me—just did not pass the laugh test. Specifically, researchers associated with the Ban…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Policy Tensor to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.