Notes on US China Policy

Grand-strategy under the global condition

The world economy in the late-twentieth century had a tripolar advanced industrial core centered on the United States, Western Europe and Japan. This structure has since been transformed by the rise of China. The Asian production network used to be centered on Japan as late as 2000. This hub-spoke system has since recentered on China.[1] And whereas the Asian core used to be smaller than the Western cores in the late twentieth century, Asia has now taken the leading position. Indeed, Asia already accounts for more than half of global manufacturing value-added, while Europe and America together account for less than a third. More precisely, China accounts for 30 percent, Asia ex. China another 17 percent, while Europe and America account for 16 percent of global manufacturing value-added each.[2] Let that sink in: China is as large an industrial power as Europe and America combined.

China’s economy may still be smaller than America’s at market exchange rates, but it is already larger than the European Union’s.[3] Moreover, Chinese living standards have begun to converge with those of the advanced economies. Real per capita income at purchasing power parity in China increased from $3,452 in 2000 to $18,188 in 2022—a rate of growth of 8.2 percent per annum. Over the same period, real per capita income grew at 1.2 percent per annum in the US and 1.3 percent per annum in the EU.[4]

The Chinese economic miracle has not only transformed the network topology of the global production system and the core-periphery structure of the world economy, it has also changed the polarity of the international system. The world at the dawn of the twenty-first century was unipolar. The United States enjoyed unambiguous supremacy is all domains relevant to the balance of power.[5] This is no longer the case. While the mature industrial countries still enjoy leadership in advanced production, China is catching up extremely rapidly in the range and sophistication of production techniques. And in as much as military power in the modern era is a function of industrial strength, the rise of China as the dominant industrial power in the world cannot fail to transform the strategic balance.

China’s military spending has averaged 1.8 percent GDP since 2000; in 2022, it was just 1.6 percent. By contrast, US military spending has averaged 3.9 percent of GDP since 2000; in 2022, it was 3.5 percent.[6] But because China’s economy has grown fifteen-fold over this period, its real military spending has increased dramatically. In 2000, China spent $46bn on defense; in 2022, it spent $298bn; or 6.5 times as much. Meanwhile, US real military spending increased from $504bn in 2000 to $812bn in 2022; or 1.6 times as much.[7] China still has some ways to go before it can close the military spending gap. And China’s balance sheet recession means that its growth may be tempered for some time. However, because China spends only 1.6 percent of its GDP on defense, it could easily compensate by spending more on guns and less on butter. If China matches the United States’ 3.5 percent, for instance, it’s real military spending will rise to $652bn, assuming zero economic growth. The Soviets paid a much higher price to secure military parity with the United States. While the US was spending shy of 7 percent of GDP at the peak of Reagan’s military buildup, the Soviets were spending an astonishing 16 percent.[8] If the Chinese decide to devote as much as the Soviets did to defense, even if the Chinese economy refuses to grow at all, Chinese military spending will rise to 3 trillion dollars. The upshot for US grand-strategy is clear: the United States cannot assume that it can outgun China by outspending it. So, before we initiate a long and costly cold war, we need to think very carefully about what we’re getting ourselves into.

What is clear from the above is that a power transition is underway in world politics. Gilpin’s motor of world history—the law of uneven growth—continues to churn.[9] For the first time since its arrival on the world stage in 1898, the United States faces a challenger potentially stronger than itself. War between the two colossi would be extraordinarily costly, even if we get lucky and it stays conventional. Indeed, we cannot assume that our efforts at escalation control will be successful once Americans and Chinese forces go into combat against each other. A dangerous tripolar nuclear order is already around the corner. What all this means is that war with China poses an existential risk to American civilization. Evading a dangerous conflict with China is a vital strategic interest of the United States. The long-term objective of US grand-strategy must be to survive the power transition in one piece. It is extremely important, then, to manage Sino-American relations with great care. We will make specific recommendations about US China policy towards the end of this essay.

Great powers don’t just jockey for influence when they’re engaged in a cold war; irrespective of the temperature of great power relations, they’re always competing for advantage and influence. Regardless of whether a cold war obtains, the United States and China are and will remain locked in long-term competition. This long-term competition is over who has greater say over world affairs. In other words, it is about the world position of the great powers.

US military primacy has underwritten America’s world position since the Soviet capitulation. But dominance is not hegemony. Hegemony is the willingness of other powers to follow your lead. The underlying strength of the American world position is due to the scale and dynamism of American civilization. With the exception of a few hermit kingdoms and revolutions masquerading as states, all the world’s nations, even our adversaries, want access to the world’s largest consumer product markets; to the deepest financial markets in the world; to our technology, skills, and know-how; to our cultural innovations. All these advantages are ultimately based on American economic preeminence. Through the American century, all nations on the planet have looked with envy at our living standards; itself a reflection of the great productivity of American civilization.

In order to fully grapple with the world conjuncture, we need to truly comprehend that we are no longer alone — Chinese civilization has revealed itself to be as dynamic as American civilization. The long-term influence of the two powers will turn on who turns out to be more dynamic. More precisely, the long-term competition between the United States and China is about productivity growth. The side that sustains greater dynamism will prevail.

The Biden administration is the poster child of rule by technocrats. The best and the brightest hold the reins. What are they up to?

US elites have responded to ‘the threat from below’ revealed by 2016 by pulling out all the stops.[10] The idea is to restore broad-based growth as a conscious strategy of political stabilization. Their formula to restore dynamism and broad-based growth is twofold. First, the plan is to run a ‘high pressure economy’ with tight labor markets—understood to be the key to achieving widely-shared growth in jobs and incomes.[11] This seemed to be working for a little while before the revival of inflation eroded real incomes—Americans’ real incomes are still about 5 percent below the levels that prevailed when Biden stepped into the Oval Office.[12] Second, the plan is a full-scale industrial policy geared towards green reindustrialization. Elites fully understand the importance of restoring productivity growth and the challenge posed by anthropogenic global heating. Their formula to secure higher productivity growth and solve global heating is to invest massively in the industries of the future — particularly those involved in the energy transition.

This is all very wise, as can be expected from the best and the brightest. However, US elites regard Trump as an existential threat to the republic. And he has refused to go away. The leader of the revolt of the masses is waiting in the wings, ready to pounce. The Biden elites’ plan to counter Trump is to embrace key tenets of Trump’s worldview and thereby deprive him of his most effective discursive weapons. Specifically, Biden elites have embraced the narrative sold by Trump about American decline. The story is that the Chinese have played the Americans like a fiddle. The crisis of the American working class is due to deindustrialization, and deindustrialization is due to unfair Chinese import competition. As we shall see, this narrative is based on a stunning misdiagnosis of the American impasse. But the issue I want to emphasize at this stage in the argument is that Biden elites and American politicians in general have largely embraced this narrative. Instead of bringing attention to a compelling theory of what has gone wrong, American politicians as a class have agreed upon laying the blame on foreigners who do not look like us. The upshot is that US China policy, which ought to be governed by careful consideration of interests, risks and opportunities, has instead become strongly coupled to the logic of electoral class politics.[13]

The China Shock paper by Autor, Dorn and Hanson is of special importance to the intellectual history of the present conjuncture.[14] These scholars showed that American commuting zones more exposed to Chinese competition lost more manufacturing jobs. This has persuaded a significant portion of the American technocratic elites that free trade has hurt the American and Western working classes. But even if Autor et al.’s estimates are correct for the impact of Chinese import competition, they’ve only estimated one side of the equation. At the very least, the other side — jobs gained due to Chinese demand for American products and services — needs to be subtracted from their estimate to arrive at the net impact of our economic intercourse with China. Dix-Carneiro and coauthors found that economic intercourse with China cost 530,000 manufacturing jobs in 2000-2014, but the US gained 522,000 jobs in services, including high-tech services.[15] During the same period, US manufacturing employment declined by 5.2 million. So, the China Shock was responsible for a tenth of the decline in manufacturing employment and this loss was fully compensated by the attendant growth in jobs elsewhere.

The truth is that trade imbalances are a mathematical function of relative savings rates. The flipside of current account surpluses are savings outflows. Countries that save more than others must necessarily export their savings; conversely, countries that save less must necessarily import the savings of others. So, the reason for the Chinese trade surplus and American deficit is not Chinese duplicity or that of US firms engaged in outsourcing, but the simple fact that the Chinese savings rate averaged 46 percent since 2000, while the US averaged 17 percent over the same period. The US has a massive trade deficit with Germany for the same reason: Germany’s savings rate has averaged 26 percent since 2000.

There is an even stronger and more obvious reason to believe that trade imbalances are a total red herring when it comes to understanding deindustrialization. Employment in manufacturing has been in secular decline since Woodstock. In 1948-1969, manufacturing employed about 23 percent of the civilian labor force. It has been steadily declining ever since: manufacturing employment averaged 20 percent in the 1970s, 16 percent in the 1980s, 13 percent in the 1990s, 10 percent in the 2000s, and 8 percent in the 2010s. Even if deindustrialization is ultimately responsible for the ‘deaths of despair’ and 2016, import competition from China in the 2000s could not possibly have been responsible because causes must necessarily precede effects.[16] In fact, deindustrialization may itself be a red herring. The structural break for deaths of despair — deaths due to alcohol poisoning, drug overdose and suicide — occurs is the early-1990s.[17] In other words, the structural break occurs decades into the decline of manufacturing and a decade before the China Shock. So, deindustrialization per se cannot be held responsible for the crisis of the American working class either.

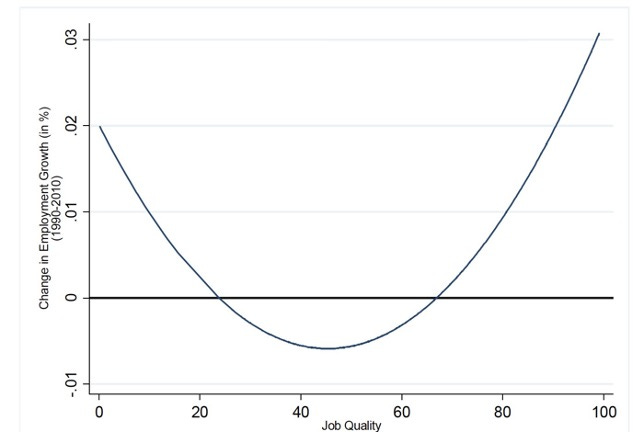

A more compelling theory pins the blame for the decline of the American working class on the transformation of the US occupational structure that is occurring around the same time as the structural break in despair: when Clinton was throwing parties at the White House to celebrate the New Economy, the US occupational structure was acquiring its present hourglass shape. As the next figure shows, the number of middle-skilled with middling pay have actually declined. Meanwhile, the number of deskilled jobs offering low pay have grown, and highly-skilled jobs for the college-educated have grown especially fast in the New Economy.[18]

What has happened as akin to the Lewisian model in monstrous reverse: instead of leaving a traditional low-productivity sector for a modern high-productivity sector, working-class American breadwinners were pushed out of middle-skilled jobs into either deskilled “dead-end” jobs at the bottom, or a life of dependence and indolence. Labor force participation for women over 20 had risen to 60 percent by 2000, where it has roughly stabilized so that participation rates of all adults are not confounded by gender composition effects from then on. In 2022, the prime-age labor force participation rate was 73 percent for college graduates, 63 percent for those with some college, 56 percent for high-school grads, and 45 percent for high school dropouts. Let that sink in: four out of every nine high-school graduates in their prime working years are no longer even looking for a job. These workers are almost certainly discouraged by the dead-end jobs that are available for high school grads.

Occupational polarization has caused grave insults to the working-class self and to the reproduction of the working-class family. The trauma of deskilling and intergenerational downward mobility resisters in self-harm, labor market capitulation, and family instability. Family formation rates are strongly stratified by educational attainment. In 2019, only 54 percent of high school graduates were married, compared to 60 percent of those holding an associate degree, 64 percent of those holding a college diploma, and 71 percent of those with a master’s degree.[19]

These insults to the working-class self and family reproduction have exacerbated the status conflict inherent in the polarization of society around what’s called the diploma divide. Emmanuel Todd has argued that the universalization of high school education flattened the distribution of capabilities and thereby made possible the egalitarian world that obtained at midcentury. But the spread of college education in the latter half of the twentieth century, because it was invariably limited to an advantaged minority, vertically polarized society along the diploma divide.[20] The world that emerged was not just economically inegalitarian; it added insult to injury through its allocation of social status by school achievement. Prestige-schooled meritocrats cornered the lion’s share of skill, income, and prestige, leaving crumbs for the provincial elites and working classes of “flyover country.”

I have tried to suggest what I see as the correct etiology of working-class despair and radicalization. Serious people may, of course, challenge my explanation of the crisis of the American working class. What is amply clear is that China is not responsible for this catastrophe. We did this to ourselves. The problem is endogenous to our civilization. It lies in our arrangements. In order to dig out of this hole, we need an honest reckoning with the underlying problem. Blaming foreigners is the refuge of scoundrels like Donald Trump. It has no place serious debate over high policy.

I have argued so far that US trade relations, with China or anyone else, have little to do with the decline of the American working class. But US trade policy is an extremely important factor when it comes to the future of American productivity and of American influence in the world at large. As we noted near the beginning of this essay, productivity growth is the key to sustaining our world position. And as we shall see, getting US trade policy right is critical if we are to secure this overriding objective.

Decolonization allowed a hundred newly independent countries to pursue their own trade policies. Modernizing elite coalitions in most postcolonial nations tried to achieve industrialization through import substitution behind protective tariff walls. None succeeded. Not one. Zero. The ones that did manage to industrialize invariably did so out in the open, on the backs of export-oriented industries. In the cross-section of 163 countries, a 10 percentage point greater exposure to the world market is associated with 0.36 percent faster growth in per capita income.[21] The reasons for this strong pattern are not hard to discern.

In the Heckscher-Ohlin model, cross-country variation in the opportunity cost of production is the source of comparative advantage and gains from trade. All countries gain from the resulting international division of labor and the economies of scale that attend specialization. Even countries that specialize in industries where prospects for productivity growth are meager stand to gain from improving terms of trade arising precisely from differential productivity growth across global industries. The dependency theory argument against Ricardian comparative advantage goes as follows. Yes, countries can gain from trade by specializing in activities where they have a static comparative advantage. But this may come at a dynamic cost because specialization in some activities, in the presence of externalities such as regional and intersectoral spillover effects, may be more conducive to future aggregate productivity growth. This argument hardly applies to highly diversified economies like the US, but it does apply with some force to countries that have a comparative advantage in commodity extraction.

At any rate, following the logic of path dependence takes us back to the very same place because the dynamically advantageous economic activities are precisely those in the tradable sector. In the United States, value-added per worker in the tradable sector has grown at 3 percent per annum over the past two decades. In the non-tradable sector, it has grown at just 0.6 percent per annum. In the cross-section of US states, a 10 percent higher share of tradables in value-added is associated with 0.7 percent higher productivity growth.[22] This is not peculiar to the United States. The same is true of administrative regions in every advanced economy: regions with greater exposure to the world market are more productive. In the cross-section of administrative regions across OECD countries, for instance, a 10 percent higher share of tradables in value-added is associated with 0.4 percent higher productivity growth.[23] Across the advanced industrial world, “regions and countries with a higher share of economic activity in tradable sectors innovate more, are more productive, have higher wages and narrow the “productivity gap” faster.”[24]

So, if you want to specialize in dynamically advantageous economic activities, there’s not much choice: you must face global competition out in the open. This is exactly how Japan, Korea, Taiwan and China managed to industrialize.

Not only is exposure to the world market strongly associated with dynamism at the level of industries, administrative regions and countries, it is also associated with dynamism at the level of firms within any given industry. It is a well-known empirical law that exporting firms are more productive than non-exporting firms. And it is not just that high productivity firms self-select into competing on the world market, although it is known that such sorting takes place systematically. Scholars have documented what’s called “learning by exporting”: productivity grows faster in exporting firms, even after controlling for prior levels of productivity. This is because exposure to the world market is not only a source of disciplinary competitive pressures on the firms but also “provide[s] them with valuable ideas and information that is not available in their domestic markets, thus enabling them to boost their subsequent innovation output and firm productivity.”[25]

More generally, the causal channel through which trade enhances productivity growth has been well understood since Melitz (2003), an academic paper that’s been cited 18,586 times.[26] The Heckscher-Ohlin class of Ricardian models explained inter-industry between countries; they could not be modified to explain the dominant pattern of trade in the core of the world economy: trade within the same industry between countries with similar factor endowments. New trade theory, beginning with the pioneering work of Krugman and Helpman, highlighted the importance of product differentiation and increasing returns to scale to explain why intra-industry trade was dominant and why most trade takes place between countries with very similar factor endowments. Melitz extended the new trade theory to explain the logic of precisely how trade enhances productivity growth. In the modern understanding, trade plays a dynamic role is fostering productivity because exposure to the world market forces the least productive firms to exit and the most productive firms to innovate harder to escape competition. This Schumpeterian logic of creative destruction and the unrelenting disciplinary force of the world market is the key to productivity growth in the advanced industrial core of the modern world economy.

There are two distinct components of intensified import competition that induce adjustments in opposite directions.[27] The first component is vertical: firms using imported intermediate goods and services in their own production processes. The response induced by the vertical component is always positive and works very much like an exogenous productivity shock. All firms that use the more efficient intermediates become more productive and profitable as a result. Market competition then ensures that most of these gains are passed on to consumers in the form of larger consumer surpluses and to workers in the form of higher wages. The second component is horizontal: it affects firms whose products are directly exposed to import competition. For low productivity firms, the horizontal component induces a negative response. Low productivity firms that find it hard to compete with imports lose market share and may be forced to exit. The response of high productivity survivors of the onslaught is usually positive. The intensified discipline of the world market incentivizes the survivors to innovate harder. Both components raise average productivity in the industry.

It may seem that the horizontal component is bad, and the vertical component is good for the home country facing stiffer import competition. But that is a myopic view of the dynamics. By driving the least productive firms to shrink or exit altogether, stiffer import competition frees up factors of production for redeployment towards more productive firms. Financial resources, embodied capital, managerial skill, and above all, the skills and knowhow of the workforce are thereby put to more productive use. This raises aggregate productivity in the industry and for the home country at large. The dynamic welfare gains from Schumpeterian creative destruction are reckoned to be three times larger than the Ricardian gains from trade.[28]

Following the US-Canada free trade agreement, the productivity of Canadian plants increased faster than before. They engaged in more product innovation and had higher rates of technological adoption.[29] The same pattern was seen following the MERCOUR agreement, where Argentinian firms upgraded their technology at faster rates than before.[30] French firms respond to exogenous growth shocks in their export destinations by patenting more.[31] British manufacturing firms respond to greater product market competition by innovating more.[32] Sectors in the UK that are more exposed to import competition exhibit higher rates of productivity growth.[33] Increased competition from Chinese firms induced European firms to increase their rates of innovation.[34] In the US, Chinese import competition led to lower profitability, but only for firms that were not engaged in R&D.[35]

One of the main findings of what’s called Schumpeterian growth theory is of particular importance to the countries of the advanced industrial core. This is the finding that “openness is particularly growth-enhancing in countries that are closer to the technological frontier.”[36] Conversely, tariff walls and non-tariff trade barriers pose special risks for the most advanced economies. Specifically, the risk posed by protectionism is that it would undermine the competitiveness of the center countries.

If the US embraces economic protectionism, as it is most definitely at risk of doing, not only will the most productive American firms face weaker import competition and therefore weaker incentives to innovate, but factors of production will also remain trapped in the least productive firms, thereby further undermining US productivity growth. And the problem cannot be contained by narrow Sino-American decoupling. If we shelter our firms from Chinese competition but, say, the Koreans don’t, then how will we compete with the Koreans? The same is true of all our allies and trade partners. We cannot escape this dilemma through clever tactics.

The upshot is that if the United States hunkers down behind tariff walls, American firms and industries will in all probability lose the productivity race. Our mistaken narratives blaming free trade for the decline of the American working class may very well cost us the very thing on which the future of America’s world position rests. We are at risk of killing the golden goose.

US foreign economic policy is important to get right not only because it is an important conditioner of the future productivity of American firms and industries. It is also a crucial conditioner of America’s diplomatic influence. And we are most definitely now engaged in a struggle for diplomatic influence with China.

The dollar’s role in the world gives the United States a great deal of power. We have abused this power for a long time with our overreliance on the economic weapon to discipline confrontation states. But with the Russia sanctions we crossed a line. The freezing of the assets of the Russian central bank in particular was a signal moment not just for our adversaries but also third parties and even allies. Everyone’s been put on alert: your dollar assets are no longer safe; they can be seized at any time. Put another way, at a stroke, our ill-considered resort to unrestrained economic warfare has undermined the status of the dollar as a true safe asset. No self-respecting country will tolerate that sort of blatant erosion of sovereignty for long. The template for the development now afoot is what happened in the aftermath of the Asian financial crisis of 1997-1998. The US, acting through the IMF, was so heavy-handed that not just the Asian countries in trouble but countries worldwide resorted to systematic reserve accumulation as insurance against our dictat. One general response this time around is that countries around the world have begun signing up for alternative payment systems being articulated by the Chinese so that they have somewhere to go if the crazy Americans turn on them.

Our abuse of the economic weapon is squarely responsible for this tendency. And we are now exacerbating the dynamic by further initiatives to garrison the world economy. The world had greeted the Biden administration with evident relief. That relief has given way to horror as the world has come to understand that Biden in bent on further articulating Trump’s economic rearmament. And then there’s the very real possibility of further instability in US policy. In a sense, this diplomatic fallout has already obtained. It’s hard to see how we can persuade anyone that US policy will be reasonable for the foreseeable future.

And it is not just the hyperactivity of our economic warriors. Because other countries now have excellent reasons to doubt the tottering US commitment to an open world economy and perceive great risks from US policy instability, they’re begun to embrace the second-best option: closer ties with China. Indeed, the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership, the China-backed trade deal, has been ratified by Japan, Korea, Australia, New Zealand and all of Southeast Asia.[37] Dozens of nations are signing up to join the BRICS, an institution that has suddenly emerged as a geoeconomic and geopolitical bloc of Chinese led anti-Western resistance. Some of this is surely the gravitational pull of the Chinese pole. But the entanglement of US trade policy with class politics is not an insignificant push factor in this equation.

The risk is that, with the Sinophobia being fanned irresponsibly by both parties, the United States will dig itself into a deeper hole. If Trump comes back into office, he will almost certainly bring in committed economic isolationists like Oren Cass.[38] One of his signal ideas is to impose a 10 percent tariff on all imports, to be increased by 5 percent annually until the deficit is closed. This trade policy, arising from a misplaced fetishization of the trade balance, is a recipe for economic and geopolitical suicide. The erosion of US productivity will come later. What will begin immediately is an irreversible process whereby China will replace the United States from the center of the world economy. With the exception of our nearest neighbors, China is already everyone’s largest trade partner. If the US hunkers down behind a great big tariff wall and China remains open for business, China will replace the United States from the center of the world economy. Make no mistake: if Oren Cass gets anywhere near the cockpit, we will almost certainly lose our world position.

Actually, we’ve played a version of this game before. American politicians wrongly seized on international economic intercourse as the source of the instability in the early-1930s. We built a great big tariff wall and pushed all other powers into autarchic grand-strategies that ultimately led to the radicalization of world powers and the catastrophe of the midcentury struggle. The lesson that Cordell Hull drew from that catastrophe was that preserving the open world economy was essential to the stability of world politics. This is why the greatest generation invested all its political capital into resurrecting the open world economy. That was why the United States created the World Bank and the IMF. Before we again destroy the world that we ourselves created, we need to revisit the original logic that governed the American articulation of global institutions.

One important lesson that was learned in the long decades of international economic liberalization championed by the United States was that it was better to be an agenda-setter than a trade warrior. As Adam Posen explained, “In big-league sports, the best job is to be league commissioner. As commissioner, you make money whichever team wins or loses on a given day, you are welcome at every stadium (even if occasionally booed), and you can ultimately decide the big questions of how the game is played and who is allowed to own a team. If you instead become identified with a single team, sometimes you win, sometimes you lose, but most importantly, others have an interest in your losing.”[39]

The message here is not that the US is at risk of squandering its agenda-setting role in the world economy. We’re well beyond that. The message here is that, in the perception of the world powers, the United States has already abandoned its role as the authoritative agenda-setter of the system. If the US world position is to be shored up, this mantle must be reclaimed—we have already squandered it.

In order to grapple with the direction of US China policy at present, we need a basic picture of Sino-Americans relations and the role they have played in US world policy over the past century or so. Our interest in China dates to the turn of the century when John Hay authored the Open Door notes. We declared that we were opposed to any foreign power acquiring a dominating position in China. The Japanese attempt to dominate China in the 1930s led to the breakdown of Japanese-American relations. Ultimately, through our unrestrained use of the oil weapon we forced the Japanese to fight us. The real bone of contention in the Japanese-American war was our disagreement over China. In fact, Chiang Kai-Shek became a sort of permanent American client. We even forced the other powers to accept a permanent seat for China on the UN Security Council, not because this ravaged war-torn country was a great power, but because we wanted to control the balance of votes at the UNSC. Later, when we lost China to the communists, Chiang withdrew to Formosa and became our semi-permanent headache. Immediately thereafter, uniformed American and Chinese forces fought it out on the Korean peninsula. We should not forget the fact that they fought us to a draw when their per capita GDP was a mere $600.[40]

The Soviets were the main US adversary until the German question was finally put to bed in the panicked aftermath of the Cuban Missile Crisis. Thereafter, China became the central object of US securitization. The Vietnam war was, of course, in part a proxy war against China. It would not be outlandish to suggest that the reason why the best and the brightest of the Kennedy-Johnson administration embraced the harebrained idea of defending South Vietnam at great cost was to defeat Mao’s world revolution by demonstrating that “wars of national liberation must fail.”[41] This was a cul-de-sac because of an anthropological fact: the Vietnamese were simply not going to transfer the “mandate of heaven” from Ho. For the same reason the West never had a chance in Afghanistan—the Pashtun tribes were never going to abandon the Taliban. The Vietnam catastrophe, when it was not otherwise destroying the midcentury world, ushered in a period of democratization of US security policy. More precisely, Congress began to impose some discipline on the presidency (Nixon’s impeachment, the Church Committee and so on), which is what drove Reagan’s security policy underground. Counterinsurgency was resurrected and turned upside down into “low intensity conflict” whereby the US attempted to destabilize communist regimes through deniable proxies (whence the Iran Contra affair). It was all run out of Vice President Bush Sr.’s office.[42]

Back to the Sino-American breakthrough in the early 1970s after US defeat at the hands of the Chinese proxy. Kissinger abandoned South Vietnam and secured a modus vivendi with Mao. Kissinger’s revolution in US China policy exploited the Sino-Soviet split to attain a favorable great power balance: in a three-power system, it is mathematically advantageous to be closer to both the powers than they are to each other. The flowering of Sino-American relations was consummated by the late-1970s. The last of the wars of the Chinese communists was a punitive expedition against Vietnam that we secretly supported. What consummated the modern arrangement of Sino-American relations was China’s new world policy. China abandoned the cause of communist revolution in favor of peaceful coexistence and economic integration with the West.

The main conditioner of Deng’s revolution in Chinese world policy, eighty years after Hay had formulated our Open Door Policy, was Sino-American détente. Indeed, it could not possibly have obtained without it. Sino-American détente ushered in a half century of peaceful security relations in East Asia called the Asian peace.[43] China used a steppingstone strategy to open up to the world market. In fact, we persuaded the Chinese to gain exposure to the world market, dragging them kicking and screaming all the way. This process of cajoling was consummated by the turn of the century. China’s accession to the WTO was an achievement of US China policy sustained over three decades since Kissinger’s foreign policy revolution.

Exposure to the world market ignited a productivity miracle in China. This productivity shock was greatly beneficial for all concerned through one direct channel—the vertical component captured by the share of intermediates in value-added. Any firm that used Chinese intermediates to make anything could now do so more efficiently and at greater profit. Much of the gains were no doubt passed on as consumer surplus and lower prices. In fact, the odds are better than even that the disinflationary impact of China’s productivity miracle was responsible for the two decades of global price stability prior to the present inflation. The world market as a whole became a lot larger due to the rise of the Chinese economy. That too benefited all concerned. Most importantly, as a result of China’s productivity miracle, American industrial firms became more productive. As argued above, the China Shock is a red herring. The real issue is whether we can remain more productive than the Chinese. Had the US not shared in the positive global externality of China’s productivity miracle, the productivity of American firms would have been that much lower.

The horizontal component of exposure to the world market—low productivity firms going out of business because of import competition—is a bitter pill to swallow. After all, situated working-class communities are themselves reliant on exposure to the tradable sector in the concrete form of situated establishments. Being in the tradable sector, these are establishments with direct exposure to Chinese import competition. We have seen that the exit of low productivity firms and the attendant reallocation of skill and capital towards high productivity firms (together with the greater incentives to escape competition for survivors at the frontier) all conspire to raise American productivity. Because we’re engaged in a long-term competition that turns on productivity growth, we should swallow this bitter pill.

Situated communities that are affected by firm exit are at high risk of labor market capitulation and should be assisted in transitioning into alternate employment opportunities. Lump sum checks in the mail for workers affected by plant closures may be an attractive policy to compensate those at the receiving end of this bitter pill without removing their incentives to seek alternate employment. We should also explore other promising ideas to encourage workers who lose their jobs as a result of firm exit to return to the labor market. But we should think bigger than just compensating the “losers” of globalization. What we should really consider doing is attacking the root of the problem plaguing the American working class: how can we reverse the occupational polarization that is the motor of American despair?

The hourglass occupational structure may be a consequence of the information technology revolution. The technology enabled routinization of production processes of both goods and services. Both men and machines were automated. Machines were automated with code. Workers were automated through routinization of tasks, thereby increasing the scale of operations that could be brought under the precise control of highly-skilled managers. An unanticipated consequence of this development in technics was the vanishing of middle-skilled occupations and the systematic deskilling of the American labor force. As we argued above, this is the correct etiology of the crisis of the American working-class.

The intellectual problem here is the implicit assumption that technology is an exogenous force and not susceptible to policy solutions. This premise is wrong. Technology is endogenous to our institutional arrangements. We can design them to incentivize certain classes of technologies and discourage others, for instance, through favorable or unfavorable tax treatment. A carefully-designed technology policy ought to be one of the pillars of open-ended American developmentalism.

A rather direct form of attack would be to force the pace of the automation of all routine tasks. This would evacuate routine tasks in job task-bundles, thereby reducing the incidence of deskilled jobs. Human workers are great bundles of skill. Using them as automata is a poor use of their human capital. If we can force the pace of automation, we can get rid of deskilled dead-end jobs sooner and reallocate our tremendous human capital towards more productive activities. This policy also works with the grain of technology and markets—the automation of routine tasks in both blue-collar and white-collar occupations is already well underway. The idea that somehow human jobs will vanish due to competition from robots and AI is a luddite fallacy. Automation does not cause aggregate job losses.[44] Rather, automation reconfigures what tasks are bundled together as jobs, increasing their creative content, reducing drudgery, and making them more rewarding for workers.

Policies aimed at reversing occupational polarization will require time to work. Policy formulation and administrative implementation takes time; once there is some clarity over policy, firms will need some time to solve new problems, innovate, and re-bundle jobs; workers will also need time to reskill and master new bundles of responsibilities. So, we’re looking at least a decade long process. We should aim to reskill one hundred million Americans over the next decade. As part of a broader vision of open-ended American developmentalism, we should be constantly refining our strategy to upgrade the skill-set of the American populace—for it is human capital that is the true font of productivity.

In terms of trade policy, we must try to reclaim our role as the agenda-setter. This involves shouldering the responsibility of articulating arrangements for the community of nations as a whole. This would require some tolerance of what may look like the loss of strategic sectors. Sheltering incompetent American automakers against Chinese competition is going to make them fatter and less competitive rather than more. At any rate, if we change the rules of the game mid-play because we start losing some valuable pieces, we shall not be able to reclaim our role as the agenda-setter. Trying to prevent China from catching up in computing by garrisoning the world economy is a harebrained idea. It has almost no chance of success. In fact, our chips escalation has already failed. It was designed to prevent Chinese firms from producing chips less than fourteen nanometers thick. They’re already making chips narrower than seven nanometers.[45] We just should let it go. All we can buy with this strangulation plan is the enduring enmity of the Chinese. We can’t actually prevent them from catching up at all. We can only run harder ourselves. That is where the focus of our policies ought to be.

What is now abundantly clear is that we cannot go any further along the road of economic rearmament and expect to reclaim our role as the agenda-setter. The harsh reality is that our allies and third parties are greatly worried about US policy. They are worried about the coupling of electoral class politics and trade policy. No one knows what US policy will be in 2025—not even Trump. Uncertainty about the basic stance of the center country is a recipe for global instability. The impasse of American class politics is forcing all nations to reconsider their world strategies in directions that undermine our world position. We should not underestimate the diplomatic challenge here. The United States cannot be both a trade warrior and an agenda-setter. We cannot both build a great tariff wall and expect to retain our position as the center country of the world economy. If we value our world position, we cannot allow this drift towards unrestrained economic nationalism to go any further.

Sino-American security relations have deteriorated markedly since Obama left the White House. We’ve essentially reneged on an implicit commitment we made to the Chinese in the 1970s that we will welcome them into the world economy we supervise. This has changed the equations that have underwritten China’s grand-strategy since the 1970s. We could very well be persuading the Chinese that they must fight us to secure their place in the pecking order of nations. By forcing the end of Sino-American détente, we’re placing the Asian peace at risk.

In terms of our core security strategy in Asia, I believe we should hold the line at the territorial status quo because any withdrawal of our defense perimeter at this stage is fraught with hazards. This means that we must be prepared to defend Taiwan, the linchpin of our military position in Asia. Taiwan is extremely important to the American position precisely because it is so important to the Chinese. Whether we can hold the line in Taiwan is the main chance. If we’re compelled to abandon Taiwan under duress, it will destroy the credibility of our security guarantees to our Asian allies who may then very well choose to bandwagon with the Chinese. Indeed, the only thing worse for our position in Asia than leaving Taiwan to its own devices is to be compelled to do so under Chinese military pressure. The Chinese reputation for power would be dramatically enhanced if they pulled that off. And the credibility of our security commitments in Asia would be shot.

Strategic ambiguity is wise diplomatic posturing. But the central front does not admit half measures. We could hold the line in West Berlin because we put all our chips on the table. We must do the same in Asia. We can deny a Chinese sea-borne invasion even after the balance of locally-available military force turns against us because the insular geography is highly advantageous for the defender. However, we do not have good counter measures for a Chinese coercion campaign against the island.[46] That is most specifically why deterrence cannot work without reassurance. If we remove all incentives for Chinese good behavior, then it becomes a simple matter of the balance of straight power. And that balance is a wasting asset.

In fact, precisely because the favorable balance of power in Asia is a wasting asset, we cannot expect to permanently deny Taiwan to China. One way or another, we will eventually have to surrender our military position in Taiwan. The question is when and on what terms. Taiwan can only be safely surrendered as part and parcel of a far-reaching modus vivendi between the two great powers. Abandoning Taiwan without solving the problem posed by the power transition is a recipe for catastrophe. It doesn’t matter whether we think that we’re not leaving due to fear; in the eyes of our allies, adversaries, third parties—and the most important audience, the Chinese—it will appear as if we are.

The only viable path to evading a war over the Taiwan question, keeping the peace in Asia, surviving the power transition in one piece, and doing all this in ways that does not undermine our world position, is to secure a far-reaching modus vivendi with China while the balance of power is still favorable to us. We can get to that point after a dangerous nuclear crisis that scares the daylights out of all concerned—just as we did on the German question after the Cuban Missile Crisis. Or we can take stock of the potential dangers inherent in the power transition and do what we can to keep these monstrous futures firmly contained in the unexplored domain of the possibility space.

What is clear as daylight is that there is no margin for error on the Taiwan question. Any sudden and unanticipated move poses unacceptable risks to the stability of Sino-American security relations. We should not even contemplate them. And we should work to convince the Chinese that they shouldn’t either. Keeping the peace requires persuading the Chinese to not reopen the Taiwan question. And that requires a combination of deterrence and reassurance.

Taiwan is not the only place exposed to Chinese military coercion. Japan, Korea, Vietnam and India are also exposed. We need to be very careful about our extended deterrence commitments on each of these fronts. We are committed in Japan and Korea. The challenge is how to deter Chinese military coercion against Vietnam and India. The Chinese enjoy local military superiority along these fronts. We don’t want to commit American forces; we can only help from afar. But, as we’ve seen in Ukraine, that may not be enough. It would be altogether better not to push the Chinese so far that they are forced to seriously consider these counterescalatory options. That too requires a combination of deterrence and reassurance.

By irresponsibly securitizing our economic intercourse with China, we have placed a fifth of all American assets at risk of Chinese retaliation.[47] Our greatest manufacturing firms—Apple and Tesla—are especially exposed. Apple alone is now of macroeconomic significance. The destruction of Apple—the expected consequence of further deterioration in Sino-American relations—will not only tank the stock market, it might even single-handedly cause a recession. Then there are the hundreds of US firms that rely on arrangements in mainland China and on Chinese imports for their production processes. The more Sino-American economic relations deteriorate, the greater the risk to these firms. Many high productivity firms may even be forced to exit by our misguided China policy.

Just how unhinged Washington’s discourse on China has become was brought home by the balloon fiasco. Media frenzy and partisan panic led jocks in the Biden White House to persuade the president to shoot them down. The intelligence community has since concluded with high confidence that, as the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs reported, “there was no intelligence collection by that balloon.”[48] Probably the very same jocks persuaded President Biden to authorize the sabotage of Nord Stream 2, irresponsibly jeopardizing our relations with the Germans.[49] These jocks are clearly not qualified to run US security policy. The basic problem with the jocks’ approach to security strategy is that their tactical theory of history is simply wrong. No great power has ever secured a lasting advantage from cloak-and-dagger shenanigans.[50]

The Sino-American relationship is our most important bilateral relationship. It should not be mismanaged in the pursuit of partisan advantage. Nor should it be handed over to the national security jocks and their freshman tactics. There is no getting rid of China. We cannot wish away Chinese power, nor undermine it with clever tactics. Under the pain of nuclear annihilation, we have to learn to live with the Chinese colossus. The long-term goal of US China policy must therefore be to seek terms of peaceful coexistence that are consistent with our vital interests. Instead of wrecking our relations with the Chinese by trying to strangle them, we need to find more deliberate and less escalatory means to persuade the Chinese to adjust their policies where we find them unacceptable. To be sure, the Biden administration has attempted to put a floor under Sino-American relations. That’s a good start. But we need to go much further. We need to find a formula that allows us to regulate long-term competition with our world historical competitor. It is too dangerous to allow the security spiral to get out of hand for reasons of political expediency. If we must fight a long and costly cold war against the strongest peer we have ever faced, it had better be for a good reason. China is not the Soviet Union. It is vastly more powerful relative to us than the Soviet Union ever was. Before we take the leap, we need to take a good hard look at the abyss.

Details on sources and citations are available upon request.

[1]https://www.researchgate.net/publication/332446433_Recent_patterns_of_global_production_and_GVC_participation.

[2] World Bank (2023), 2021 numbers.

[3] World Bank (2023), 2022 numbers.

[4] World Bank (2023).

[5] Wohlforth (1999). “The Stability of the Unipolar World.”

[6] SIPRI (2023).

[7] SIPRI (2023). Constant 2021 dollars.

[8] SIPRI (2023) for US; Federation of American Scientists (2000) for the Soviet Union.

[9] Gilpin (1981). War and Change in World Politics.

[10] Richard F. Hamilton (1972). Class and Politics in the United States. John Wiley and Sons.

[11] Okun (1973). “Upward Mobility in a High-Pressure Economy.” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, no. 1: 207-261.

[12] NY Fed (2023). Equitable Growth Indicators.

[13] Gideon Rachman. “The real reasons for the West’s protectionism.” Financial Times, Sep 18, 2023.

[14] Autor, David H., David Dorn, and Gordon H. Hanson (2016). “The China Shock: Learning from labor-market adjustment to large changes in trade.” Annual Review of Economics 8: 205-240.

[15] Dix-Carneiro et al. (2023). “Globalization, Trade Imbalances, and Labor Market Adjustment.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics, Volume 138, Issue 2, p. 1109–1171.

[16] Anne Case and Angus Deaton (2015). “Rising morbidity and mortality in midlife among white non-Hispanic Americans in the 21st century.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 112(49), pp.15078-15083.

[17] Giles, Tyler, Daniel M. Hungerman, and Tamar Oostrom. Opiates of the Masses? Deaths of Despair and the Decline of American Religion. No. w30840. National Bureau of Economic Research, 2023.

[18] Figure from https://www.iza.org/publications/dp/9814/good-jobs-bad-jobs-whats-trade-got-to-do-with-it.

[19] https://educationdata.org/education-attainment-statistics.

[20] Todd.

[21] My calculations based on OECD data.

[22] My calculations based on data taken from OECD (2016, Regional Economic Outlook, Annex A1). Productivity growth is measured over the period 2000-2013.

[23] My calculations based on OECD data.

[24] OECD (2018), Productivity and Jobs in a Globalised World: (How) Can All Regions Benefit?, OECD

Publishing, Paris. Page 155.

[25] Freixanet and Federo (2023).

[26] Melitz, Marc J. "The impact of trade on intra‐industry reallocations and aggregate industry productivity." Econometrica 71, no. 6 (2003): 1695-1725. Citation count was obtained from Google Scholar on 2023/09/17.

[27] This discussion is adopted from Melitz and Redding (2023), “Trade and Innovation.” in The Economics of Creative Destruction, eds. Akcigit and Van Reenen.

[28] Sampson (2016), quoted in Merlitz and Redding (2023).

[29] Lileeva and Trefler (2010).

[30] Bustos (2011).

[31] Aghion et al. (2020).

[32] Nickell (1996).

[33] Aghion et al. (2009).

[34] Bloom et al. (2016).

[35] Hombert and Matray (2018).

[36] Aghion, Philippe, Ufuk Akcigit, and Peter Howitt. “Lessons from Schumpeterian growth theory.” American Economic Review 105, no. 5 (2015): 94-99.

[37] https://www.economist.com/finance-and-economics/2023/06/15/america-is-losing-ground-in-asian-trade

[38] https://americancompass.org/rebuilding-american-capitalism-provides-the-agenda-for-conservative-economics/

[39] https://foreignpolicy.com/2023/03/24/economy-trade-united-states-china-industry-manufacturing-supply-chains-biden/.

[40] Maddison, 1990 international dollars.

[41] “By 1964, after the Cuban missile crisis and before large numbers of American forces got bogged down in Vietnam, the United States looked so powerful that not only some Americans but others too (particularly Frenchmen) began to think of the world as virtually monopolar and of America’s position in the world as comparable to that of a global imperial power. The only remaining gap in military containment might be closed if the United States could demonstrate in Vietnam that wars of national liberation must fail.” Osgood (1969). Limited War Revisited.

[42] Sy Hersh (2019). “The Vice President’s Men.” London Review of Books, Vol. 41 No. 2 · 24.

[43] Van Jackson (2023). Pacific Power Paradox: American Statecraft and the Fate of the Asian Peace.

[44] https://scholarship.law.bu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1811&context=faculty_scholarship

[45] https://www.economist.com/business/2023/09/14/apple-is-only-the-latest-casualty-of-the-sino-american-tech-war

[46] Owen Cote Jr.

[47] IMF decoupling report.

[48] https://www.cbsnews.com/news/the-bizarre-secret-behind-chinas-spy-balloon/.

[49] Sy Hersh (2023). “How America Took Out the Nord Stream Pipeline.”

.

[50] On the struggle between jocks and nerds in the US security state see

https://twitter.com/policytensor/status/1647676756294336512

.

"US military primacy has underwritten America’s world position since the Soviet capitulation. But dominance is not hegemony. Hegemony is the willingness of other powers to follow your lead. The underlying strength of the American world position is due to the scale and dynamism of American civilization. With the exception of a few hermit kingdoms and revolutions masquerading as states, all the world’s nations, even our adversaries, want access to the world’s largest consumer product markets; to the deepest financial markets in the world; to our technology, skills, and know-how; to our cultural innovations. All these advantages are ultimately based on American economic preeminence. Through the American century, all nations on the planet have looked with envy at our living standards; itself a reflection of the great productivity of American civilization."

Speaking of squandering, the US and the West still enjoy great reserves of soft power, which they insist on squandering.

A brilliant essay. Much food for thought. Thank you.