Proof that Global Imbalances Did Not Cause the Financial Crisis

Debunking the net-flows paradigm

At the heart of the Trump-Biden-Khanna thesis on US foreign relations is the suspicion that global imbalances caused the global financial crisis. This is coupled to the idea that American deficits — the flipside of the surpluses run by other commercial powers — have hurt American interests. Specifically, the argument is that, whether fairly or unfairly, countries like China and Germany have “hogged” the global pie, leaving less for American families. The centerpiece of the evidence is that marshaled by Autor et al. of the China Shock fame.

I have pointed out that the whole case is much weaker than it looks. Ro Khanna stated in Foreign Affairs that the total number of “good jobs” lost to China since 2000 is 3.7m. For reference, the number of job openings have exceeded ten million in every month since July 2021. Indeed, four million Americans quit their jobs every month. For a more precise comparison, we estimate that some twenty million “good jobs” have vanished since 2000. So the Chinese contribution to the loss of “good jobs” is at most less than a fifth. This is a strict upper bound because we have not added a single “good job” from the sale of American products to China. On a net basis, which believers in the net-flows view of the world should especially prefer, there is no reason to expect that American workers have not indeed gained more jobs than they have lost because of economic intercourse with China and the rest of the world.

We have argued that financial cycles are not driven by savings gluts but by procyclical interaction between intermediary leverage and the price of property that can serve as collateral for secured lending. Shin’s banking glut hypothesis is more compelling to us as the general motor of the financial cycle, rather than any savings glut (of the oil and manufacturing exporters, corporations, or the rich). At the heart of all financial cycles is loans against real-estate assets. In particular, the financial booms at issue — mortgage lending in US and Spain etc — were not financed by a glut of savings. Without a buildup of intermediary, and indeed, household and firm leverage, there would not have been catastrophic booms of the sort that did obtain in the mid-2000s. But our theory of the case is not under investigation in the present dispatch. We’re here concerned exclusively with ruling out the net imbalance theory of instability; and more generally, debunking the net-flows paradigm of macroeconomics and global political economy.

We can more directly disprove the net imbalance hypothesis if we correctly identify a necessary implication of the theory that can be tested against the empirical evidence. At the heart of the net imbalance theory is the posited causal chain: (1) deficit countries import the excess savings of surplus countries; (2) this flood of savings fans lending booms in deficit countries; (3) the lending boom is the proximate cause of instability. We argue that (1) and (3) are true, but (2) is false. Now, if the theory is correct, the causal effect must necessarily go through the mediator. That is, lending booms must be fanned by the inflow of excess savings for global imbalances to cause financial instability. So, if we can prove that (2) does not hold, then the global imbalance theory of instability can be ruled out.

Note that (1) is obviously true, at least in an accounting sense — deficit countries must necessarily import the savings of surplus countries. (3) is the overwhelming signal in the macrofinance data and is not under serious dispute. The mediating causal claim, (2), which says that the excess savings imported by the deficit countries fan lending booms there, is at the heart of my disagreement with the old guard like Brender and Pisani, who want to save the net-flows paradigm from extinction.

We disprove (2) by testing the implication that countries running larger current accounts have higher credit gaps than countries running surpluses. This is a necessary implication of (2), which, recall, implies that booms occur in deficit countries that import the excess savings of surplus countries. Because we are convinced that real-estate is the heart and the secret soul of every true financial cycle, our main response is the mortgage credit-to-gdp ratio. But we also test whether loans-to-gdp ratios for loans to households, businesses, or both are predicted by current account balances. Our proof debunking the net imbalance theory is thus robust to the failure of our alternate hypothesis that the coupling of dealer leverage with property prices caused the financial boom that came to grief in 2008.

We test these hypotheses using the Jordà-Schularick-Taylor Macrohistory Database. Our baseline specification is a panel regression with the three year rolling average of net current account balance (exports less imports) as the feature or predictor (net balance, denoted ca), and the three year rolling average of private mortgage credit-to-gdp (mortgage-credit gap, denoted tmort) as the response. We admit country fixed-effects and cluster errors within country. We estimate our baseline model for the period 1979-2008, which can be considered a roughly-stable macroeconomic regime. But we show that our negative result is robust to alternate specifications for credit gaps and the sample period.

We find that the effect of net balance on the mortgage-credit gap is statistically indistinguishable from zero at the 10 percent level. Simply put, advanced economies with larger current account deficits do not exhibit higher mortgage-credit gaps.

More generally, we find that net balances do not predict lending to households, businesses, or the private sector as a whole. The estimated slope coefficients are all statistically indistinguishable from zero at the 10 percent level of significance. Advanced economies with larger current account deficits simply did not exhibit higher credit gaps than countries running surpluses during the decades preceding the financial crisis.

In theory, even if financial imbalances are a larger component of the financial cycle than net imbalances, the latter should have some effect on the financial cycle. We have shown that this theoretical expectation is not confirmed by the empirical evidence of the Jorda et al. panel data. Countries importing net savings do not exhibit larger lending booms than countries exporting net savings. The evidence is thus inconsistent with the hypothesis that global imbalances played any causal role in the financial instability of the late-2000s.

The net flows paradigm should be abandoned in light of the fact that the excess elasticity of intermediary balance sheets severs the posited link between savings and lending booms. More broadly, we must abandon the mercantilist idea that global imbalances have anything to do with our financial, economic and political woes. In a future dispatch, I will explain how the benefits of the Trump-Biden revolution in US foreign policy are not commensurate with the costs and risks associated with it — that the Biden escalation will likely reduce American influence in the world. In the present dispatch, we’ve shown that the net imbalance theory of instability is inconsistent with the empirical evidence. Therefore, the Trump-Biden-Khanna consensus is based on a false premise.

Robustness checks.

The following table reports within-R^2s and t-statistics for panel regressions with net balance as the feature and credit to nonfinancial sector (% of GDP, 3 year rolling average) as the response. Rows correspond to the last year and columns to the first year of the sample. All of them vanish.

The following table reports within-R^2s and t-statistics for panel regressions with net balance as the feature and credit to households (% of GDP, 3 year rolling average) as the response. Rows correspond to the last year and columns to the first year of the sample. All of them vanish.

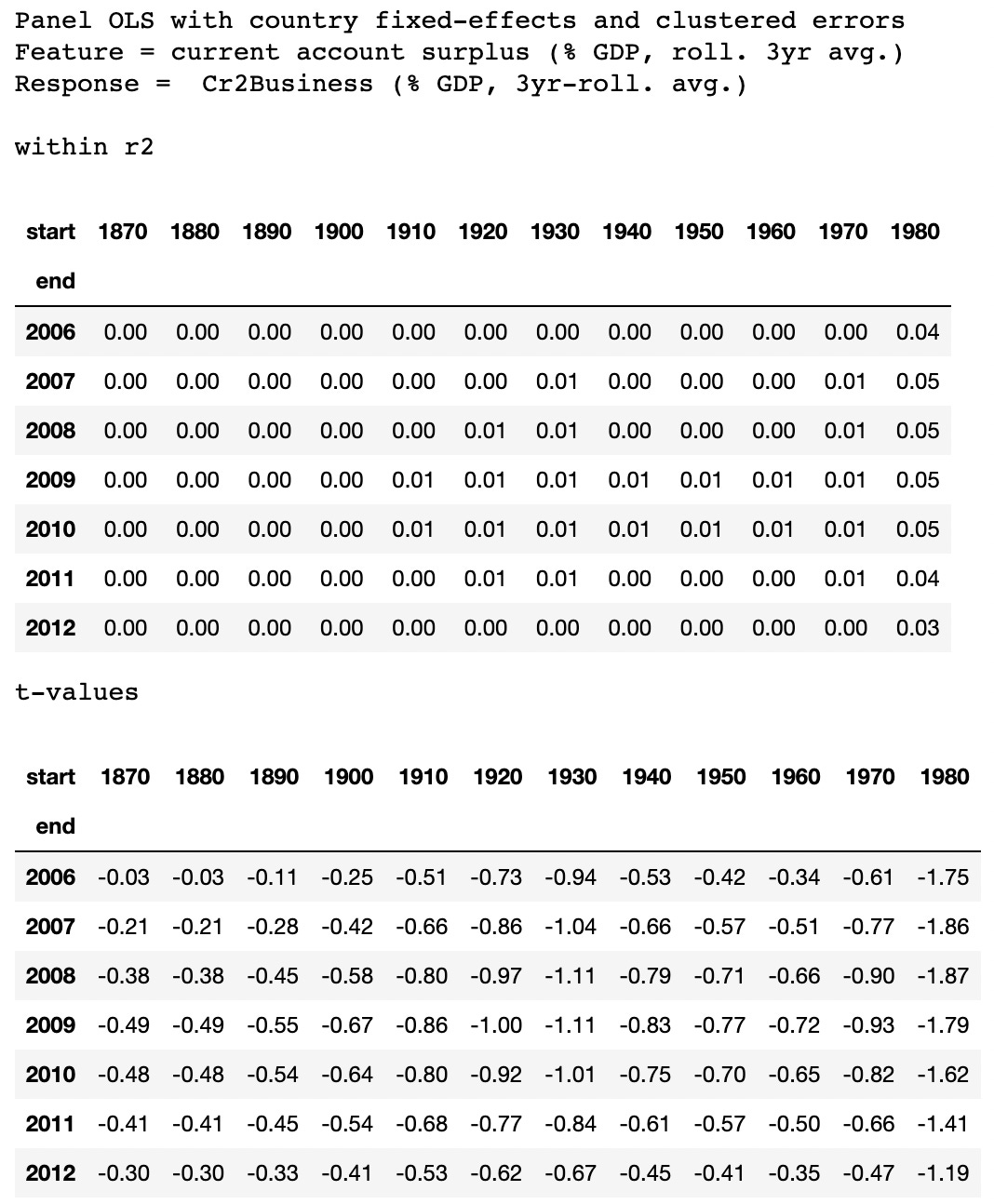

The following table reports within-R^2s and t-statistics for panel regressions with net balance as the feature and credit to businesses (% of GDP, 3 year rolling average) as the response. Rows correspond to the last year and columns to the first year of the sample. All of them vanish.

The following table reports within-R^2s and t-statistics for panel regressions with net balance as the feature and private nonfinancial mortgage credit (% of GDP, 3 year rolling average) as the response. Rows correspond to the last year and columns to the first year of the sample. All of them vanish.

There is no evidence that countries importing net savings have higher credit gaps, a necessary implication of the net balance theory of instability.

"We have argued that financial cycles are not driven by savings gluts but by procyclical interaction between intermediary leverage and the price of property that can serve as collateral for secured lending. Shin’s banking glut hypothesis is more compelling to us as the general motor of the financial cycle, rather than any savings glut (of the oil and manufacturing exporters, corporations, or the rich). At the heart of all financial cycles is loans against real-estate assets."

Dr. Minsky, please pick up the white courtesy phone, Dr. Minsky...

Anyway, the reason that Khanna, Trump and Biden push the outflows thesis is that this allows foreigners to be blamed for economic woes, rather than politically connected domestic interests.

Somewhat tangentially, China's WTO accession had zero effect on the 50-year rate of fall in manufacturing's share of the US economy.