Seeing Like BlackRock

The view from E 52nd St

The self-congratulation of US elites was at a historical peak in the late-1990s. While Clinton threw parties at the White House to celebrate the success of the New (Hourglass) Economy, Alan Greenspan was hailed as a living Saint. By mid-decade inflation expectations had become anchored on target. But by the end of the decade, expectations about future states of the world, as captured by equity valuations, got completely deanchored from fundamentals. The unprecedented financial boom would prompt Shiller to author Irrational Exuberance.

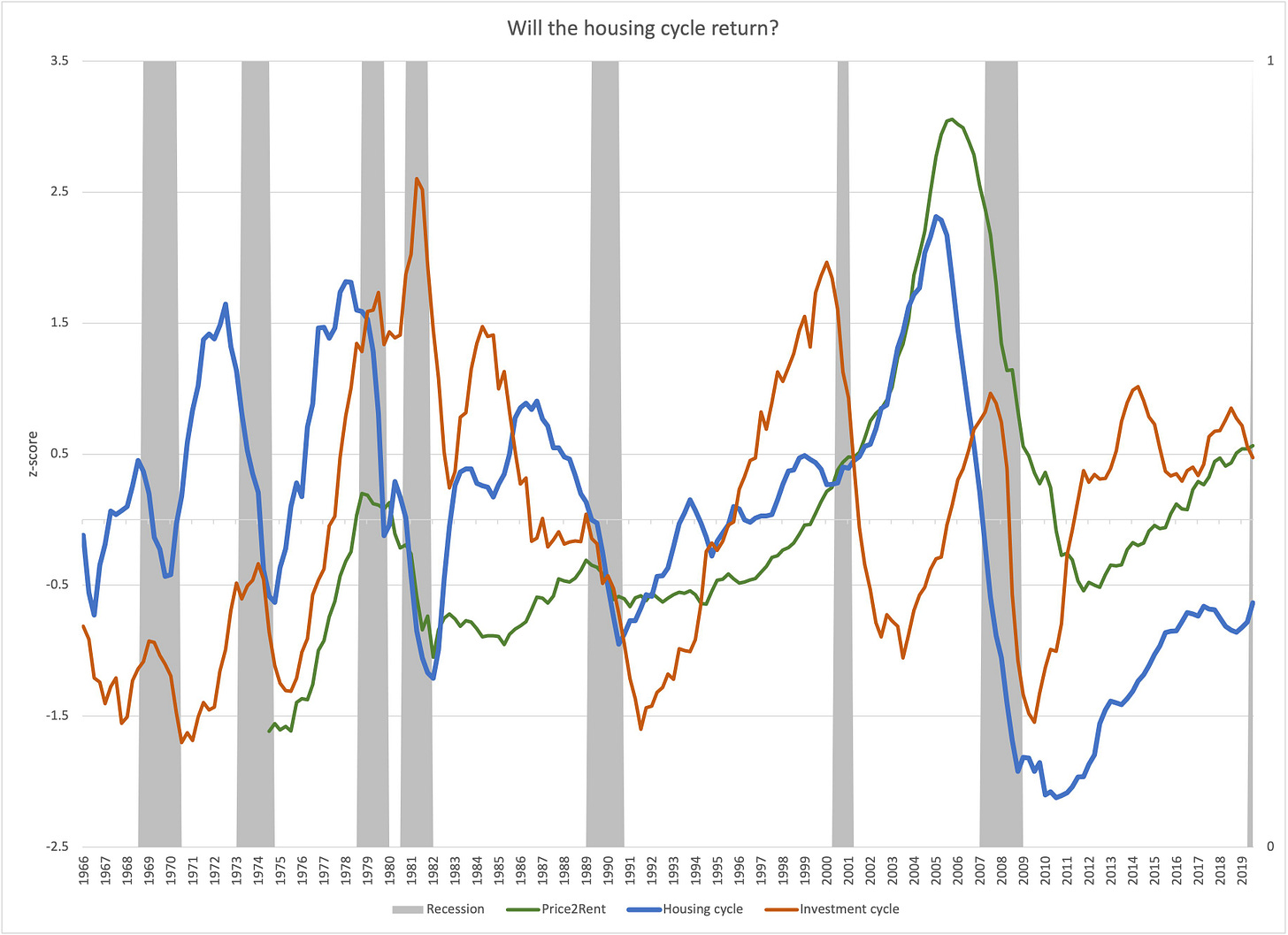

The stock market bubble burst in March 2000. The recession was uncharacteristically mild and short-lived because, unlike most recessions, it was not caused by the turn of the housing cycle. It was instead a recession straight out of economic theory—caused by the turn of the investment cycle. In the following chart, the housing and investment cycles are proxied by the shares in GDP of private residential and non-residential fixed-investment respectively:

Wall Street and Silicon Valley were plunged into crisis in the early years of the 21st century. Out of this crisis would emerge three structures of power that would condition world order in the following decades. In 2003, JP Morgan solved the problem of manufacturing safe assets at scale from residential mortgages. In the same year, Google articulated the business model of platform surveillance just as the surveillance state was being articulated by the NSA. Also in 2003, the SEC issued the proxy voting rule mandating asset managers to vote in the best interests of the asset owners they represented at shareholder meetings.

All three structures of power that emerged had to do with the problem of scale and information: power was to be exercised from a great height over millions or even billions of people. The problem in each case was that the holders of power did not have information on each particle in the detail. It’s not that the data didn’t exist. It was just too immense, too high-dimensional to examine in full detail—you could only probe it along zero-dimensional subspaces. To the giant banking, surveillance and asset management firms, each particle was as good as invisible. The professional class elites who ran these systems of power were forced to reduce the problem to drastically lower dimensions. Put simply, they simplified it by reducing it to bare bones: rating classifications for complex mortgage-backed securities, simple models of your future behavior, ESG. There was an ocean of data folded away in each mortgage-backed security, into each model of behavioral prediction, and behind each taxon in ESG rating classifications.

As the financial boom got underway, ratings got decoupled from the actual credit quality of the millions of mortgages that were used as raw material to manufacture safe collateral at scale for the wholesale funding market. The bankers’ house of cards collapsed as credit risk made its way to rehypothecation flywheel. The global financial crisis began in earnest with the Lehman bankruptcy; in Europe, it would morph into a sovereign debt crisis as bank debt was nationalized. The global financial crisis in turn would kick off a series of political crises as the legitimacy of US elites, already eroded by the catastrophe of the Iraq War, collapsed. The Arab world soon erupted in a systemic crisis of state legitimacy. Angry working classes would bring right-wing authoritarian rulers into power across continents.

The power of Zuboff’s surveillance capitalism first become evident in the false dawn of the Obama presidency. Google-White House relations were very cosy. But it was not until after the catastrophe of 2016 that the full power of the platform panopticon would be revealed. The professional class became engulfed in a series of escalating moral panics in the Trump years. Things came to a head in the summer of 2020. A unity of interests had come behind Biden to get rid of the offensive fellow in the White House. No stone was to be left unturned. America’s elites, frantic at the threat from below revealed by 2016, openly demanded from their thousand fortifications that the platforms censor speech and search at scale. Google and Facebook began openly censoring politically inexpedient content. The established media was not far behind. Virtually all of the 618 riots went unreported in the paper of record. The effort at thought control may not have been particularly successful, but it was perceived as such by angry working-class Republican partisans, thus splitting the population into belief silos along class-partisan lines. The erosion of the legitimacy of media and social media institutions would be reflected in the Capital Riot—a good quarter of the population had come to believe that the election was really and truly stolen from a beleaguered president.

At the same time as Facebook and Google were perfecting the techniques of manipulating information flows, the rise of asset managers was transforming financial intermediation. In 2009-2018, while actively managed funds saw an inflow of $200bn, some $3,400bn flooded into passive funds. Due to economies of scale in managing assets passively, the liquidity benefits of larger funds, and the fact that any innovative index can easily be replicated by the market leaders, most of the bonanza was cornered by the Big Three—BlackRock, Vanguard, and State Street.

The logic of passive investing meant that an unbounded amount of money could be managed from a single center of power. Whereas banks with balance sheet capacity in the hundreds of billions of dollars had dominated high neoliberal financial intermediation, the new species of intermediaries became an order of magnitude larger. It was a textbook instance of speciation due to multiple local optima in the fitness landscape. (Slide from a fascinating recent paper by James Stroud.)

Together the Big Three came to control a larger and larger share of common stock in the largest publicly listed corporations. BlackRock alone has $9tn in assets under management—only the United States and China have larger economic size. Together, the Big Three control at least 20 percent of the S&P 500 outright. This understates their influence because most shareholders don’t participate in shareholder meetings, while the asset managers are required to do so by the 2003 SEC proxy voting rule. Their share of votes cast is thus more than 25 percent. Given that the typical shareholder vote has a margin of 10 percent, the Big Three have gained veto power over corporate governance. Their influence is, in fact, even greater: corporate boards preemptively respond to their policy positions and private engagement at scale ensures continuous influence of the Big Three over corporate affairs.

The diagnostic character of the passive species is that, unlike small shareholders, patient intermediaries, private equity firms, dealers and hedge funds, they have no exit option: they have no choice but to stay invested in any and every firm listed in the indices they track. This makes them truly patient intermediaries; indeed, permanent investors in the largest firms that the indices track. Both BlackRock and Vanguard control at least 5 percent of every S&P 500 corporation.

In effect, the Big Three exercise something akin to state authority over the largest corporations that account for the vast bulk of economic activity in the tripolar core of the world economy and increasingly on the periphery. This degree of concentration of corporate control has not been seen since the days of J.P. Morgan. Indeed, Fink enjoys more power than J.P. Morgan did in 1907.

In order to understand the view from E 52nd St, you have understand the implications of scale, the no exit option, and the regulatory landscape. Because the proxy voting rule requires them to vote in their clients’ best interest, they have no choice but to develop policy positions on corporate governance and implement them across their holdings in a way that they can defend in front of the SEC. In order to do that, each of these asset managers has set up what they call Stewardship teams. The BlackRock Stewardship team has some fifty investment professionals who decide BlackRock’s policy on corporate governance in collaboration with investment teams.

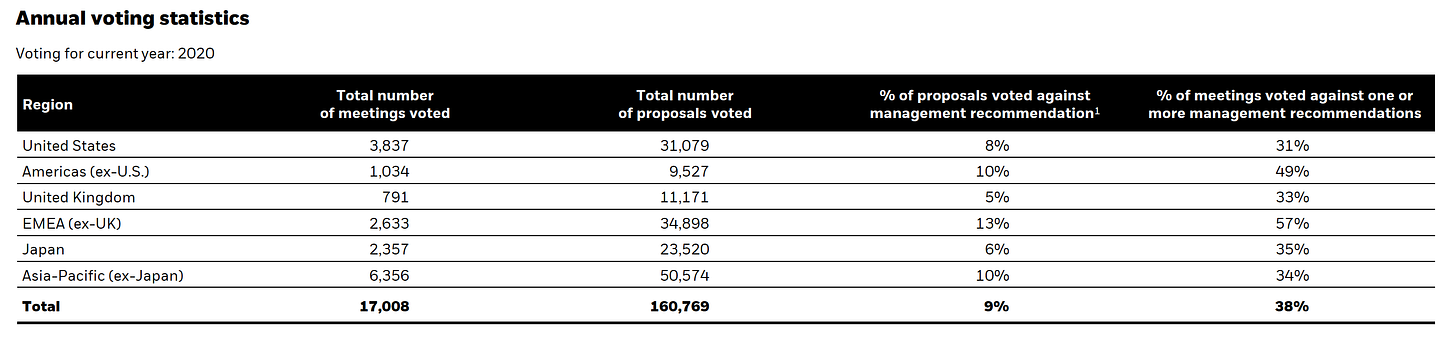

In 2020, BlackRock voted on 160,769 proposals at 17,008 shareholder meetings. It is here that the problem of scale becomes absolutely paramount. It is physically impossible for the fifty members of the Stewardship team to make decisions informed by firm-specific information. To them, each firm in their portfolio is sort of like what each mortgage was to MBS traders in the mid-2000s, or you and I are to Facebook and Google. They can’t actually see the particles from their great height. They have no choice but to develop very broad principles of global governance. Moreover, each deviation from the uniform implementation of the asset managers’ global principles of corporate supervision is potentially subject to regulatory and legal challenges. Therefore, despite claims to the contrary, they are informationally constrained to implement a one-size-fits-all disciplinary approach on all firms they control.

Once one has grasped the view from E 52nd St, the logic of ESG becomes clear. The rise of ESG is the result of the BlackRock’s search for a rational order in the dispatch of its fiduciary duties imposed by the SEC. As a permanent investor in practically the whole of the corporate economy, the paramount interest of E 52nd St is the long-term risk-adjusted performance of the corporate economy as a whole. In this sense, BlackRock is a truly patient intermediary.

This does not mean that BlackRock is committed to solving the climate crisis or broad social reform per se. The goal of ‘incorporating ESG factors into the investment process’, as the Stewardship team puts it frankly, is not maximizing social welfare or getting off the hockey-stick of doom, but instead ‘enhancing risk-adjusted financial performance’. By construction, then, ESG cannot serve as a reliable signal of contribution to decarbonization and climate resilience because what it is measuring is risks to the financial performance of corporations, not contribution to decarbonization and climate resilience. This is true not only of asset managers’ ESG metrics—it is also true of the methodologies developed by MSCI and Sustainanalytics.

It is not clear whether BlackRock is a friend or a foe. On the one hand, it is a truly patient intermediary with a strong interest in overall long-term performance of the corporate economy. It is thus not surprising to find Brian Deese, the former Global Head of Sustainable Investing at BlackRock, serve as the chair of Biden’s National Economic Council, and more generally, to find BlackRock playing the role that Google played in the Obama administration. On the other hand, it is unclear whether the Stewardship team, Brian Deese, Secretary Yellen or anyone in the White House actually understands the full scope of the challenge posed by the climate crisis. Are Larry Fink’s letters to CEOs urging action on climate for real or for show? Does E 52nd St have a plan?

As of writing, it is not clear whether BlackRock is an ally or an adversary in the climate fight. The alignment of forces will become clearer as the rubber meets the road. Tim Sahay and yours truly have proposed a standalone public ratings agency whose ratings will serve as a public signal of which projects are truly green and which are dirty. Zane Rubaii, an economist in training, has joined us in the project. We’re working in consultation with Saule Omarova and Yakov Feygin on a white paper that will formally propose the ratings agency to Congress and spell out how it can be implemented in detail. This will serve as a small test of BlackRock’s intentions. If E 52nd St truly gets it, they will back the proposal. If they oppose it, we will know.

As a member of the feline-american community, it seems to me that one of the differences between the impact of the dot-com implosion vs The Great Recession was the difference between an equity bubble and a debt bubble.

Cue up Hyman Minsky vs Modigliani-Miller.

My understanding is that ESG initiatives largely aspired to lower the ‘cost of energy’ across the value chain of a company’s ecosystem. This would enable more business efficiency (at least that was the theory and the aspiration). Based on how scope 1,2,3 and other ESG reporting works elements of E and S in ESG were proxy to something else.