The Generalized Dutch Disease

Evidence from the cross-section of US states

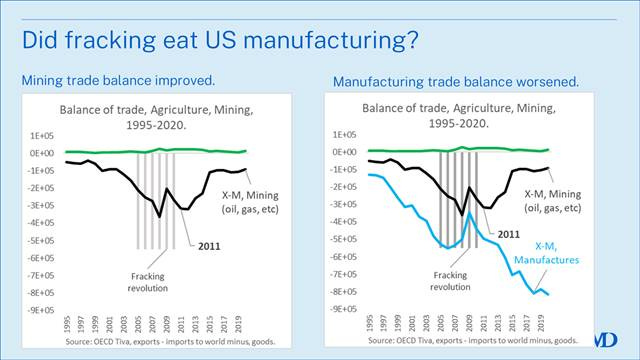

Richard Baldwin’s FactFull Friday last week suggested that the US was suffering from the Dutch Disease. He showed that the decline of US manufacturing trade balance was mirrored by the improvement in the mining trade balance.

His dispatch led me to posit a generalized Dutch disease whereby booming sectors like finance, real estate, oil, and compute could make US manufacturing in particular and tradables sector in general less competitive.

I have a theory I am exploring. It was inspired by [Baldwin’s] last Factful Friday. The idea is that the Dutch Disease is a particular instance of a general phenomenon.

Basically, massive booms suck in factors of production, bidding up factor prices across the economy, driving unit labor costs higher, making the country less competitive in the tradable sector. Activity in tradables shrinks, while activity in non-tradables expands. This effect may be exacerbated by currency appreciation, but that is not strictly necessary; the loss of competitiveness happens regardless.

My thesis is that the three gigantic booms—housing & finance, fracking and more recently, compute—have done precisely this.

The allocation of capital to tradables has fallen from 18.6% in 1998-2002 to 16.4% in 2015-2023. Labor allocation to tradables has fallen from 20.0% to 17.2%. Meanwhile, TFP growth in tradables has fallen from 1.92% in 1998-2007 to 0.76% in 2011-2023.*

Much of the decline of US manufacturing may be due to the great sucking sounds of these booms.

*Using value-added weights. BEA Industry KLEMS data.PT on Twitter.

In what follows, I document that the evidence from the cross-section of US states is consistent with the hypothesis of the generalized Dutch Disease.

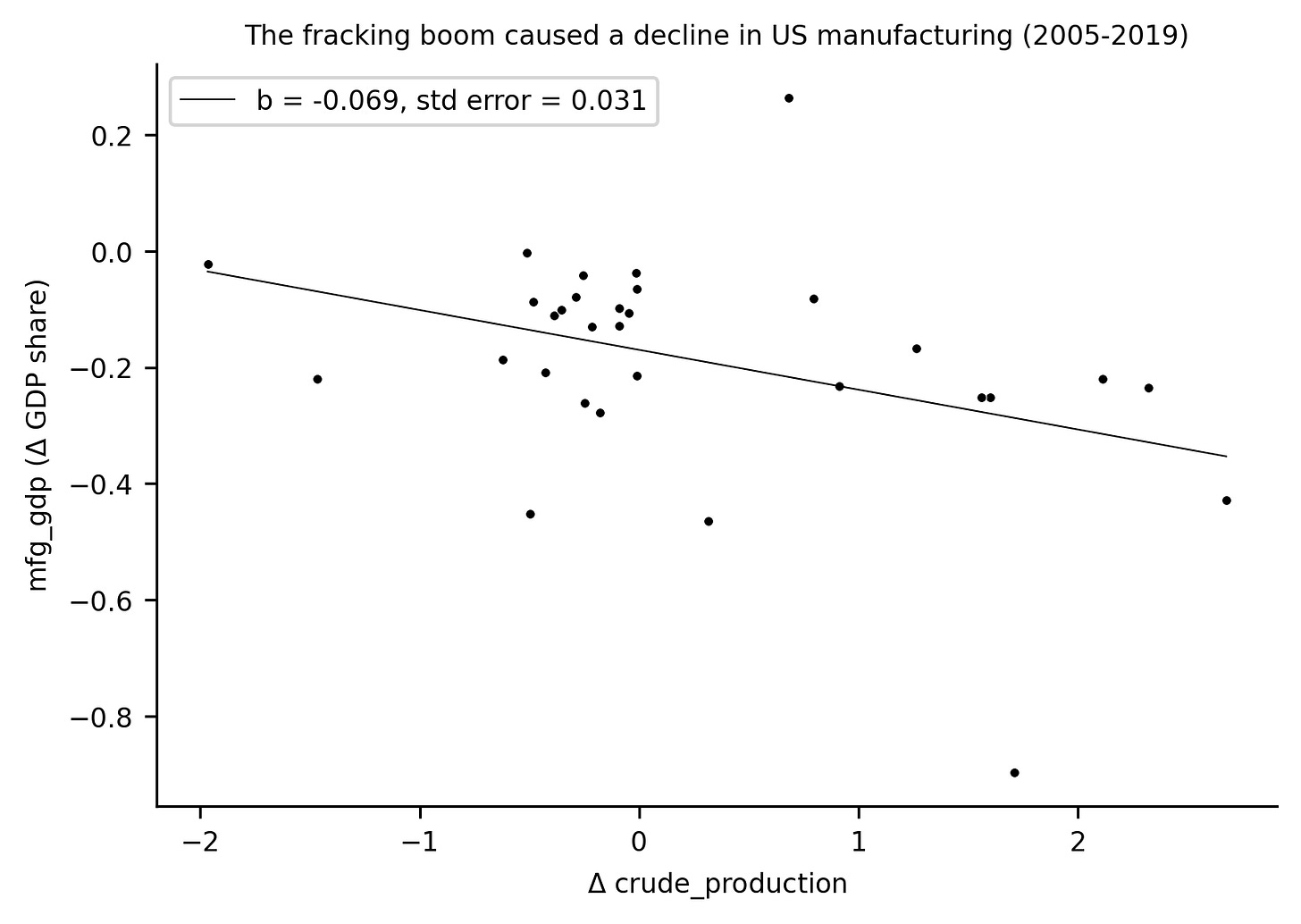

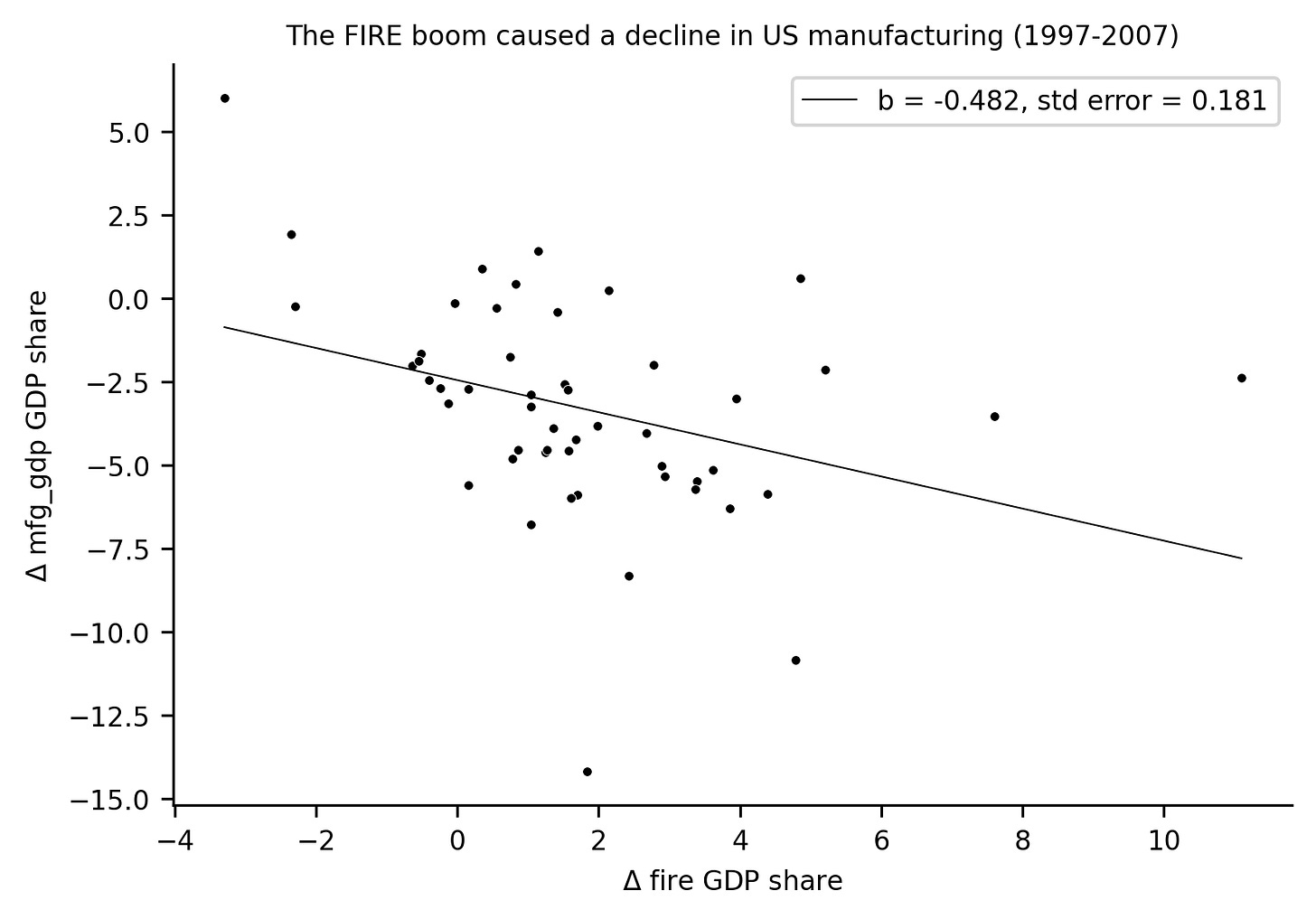

We obtain data on GDP by state-industry-year from the BEA. We compute the shares of FIRE and manufacturing in state GDP by year. We obtain crude oil production by state-year from the EIA. If my hypothesis is correct, we should find a negative association between growth in crude oil production and FIRE sector growth on the one hand and manufacturing share of GDP on the other. For the financial boom, we compute log changes in manufacturing and FIRE shares of GDP for 1997-2007. For the fracking boom, we compute log changes in crude oil production and manufacturing share of GDP in 2005-2019. We do not have the data yet to test the hypothesis for the present capex boom in compute.

We find the predicted gradient for the fracking boom. Manufacturing share declined more in states that saw a bigger expansion of oil extraction. The gradient is modestly large (b=-0.069) but statistically significant (t = -2.20). One log-point increase in crude production is associated with a 0.069 log-point decline in the manufacturing share of GDP. The modesty of this effect is expected. The US is one of the most diversified economy in the world; it is not in the same position as the Dutch, British or Norwegian economies.

We find a much stronger association for the financial boom; fitting so for the one of the largest financial booms in history. The gradient is large (b=-0.48) and statistically significant (t = -2.66). One log-point increase in FIRE sector share of GDP is associated with a 0.48 log-point decline in the manufacturing share of GDP.

Note that the above estimates are entirely cross-sectional and therefore do not include one of the principal channels through which the Dutch Disease works: the exchange rate channel. High global demand for US energy in particular strengthens the dollar at the margin, making other US-produced tradables less competitive on the world market. This factor is shared by all states and is therefore not visible in the cross-section of US states.

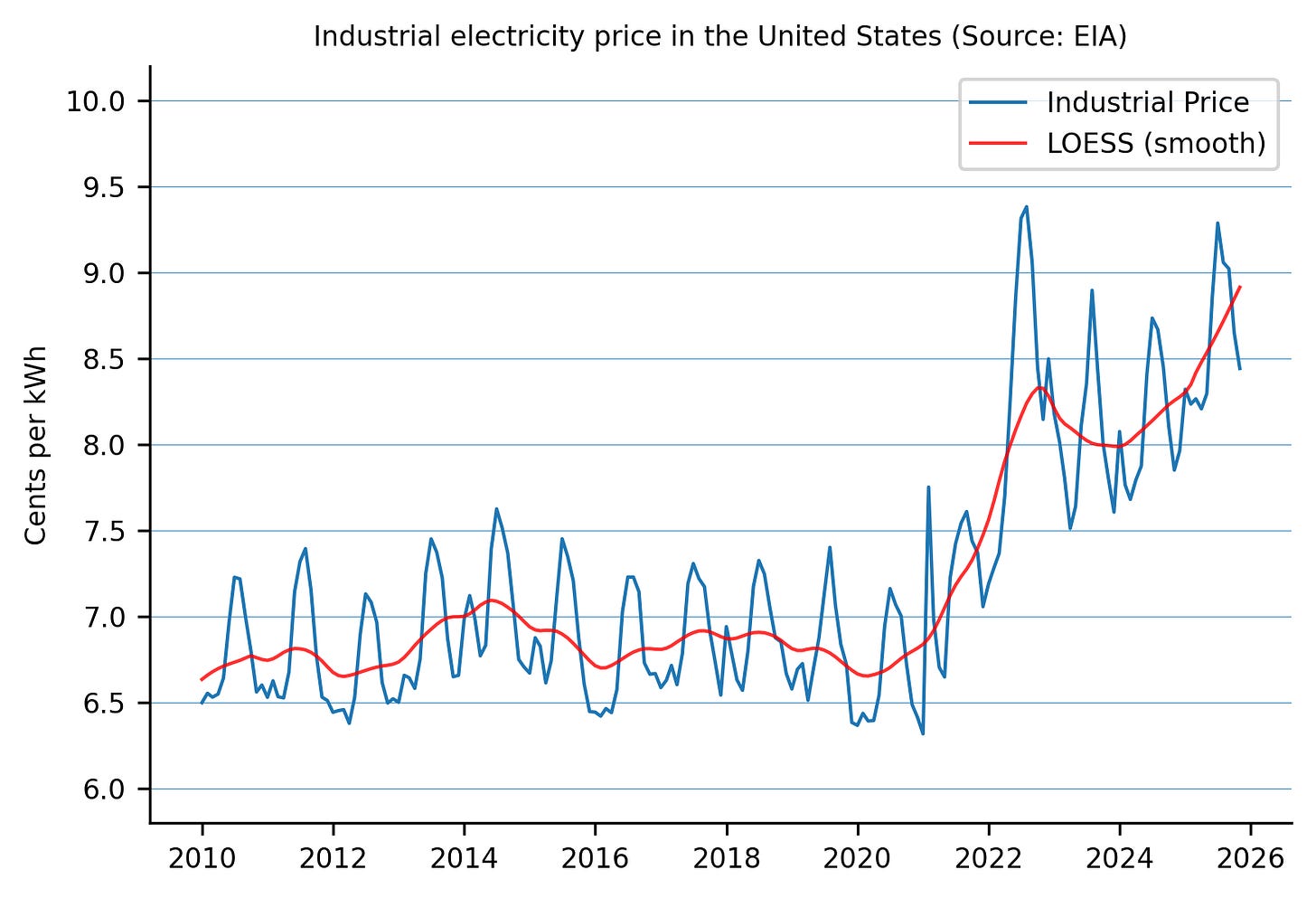

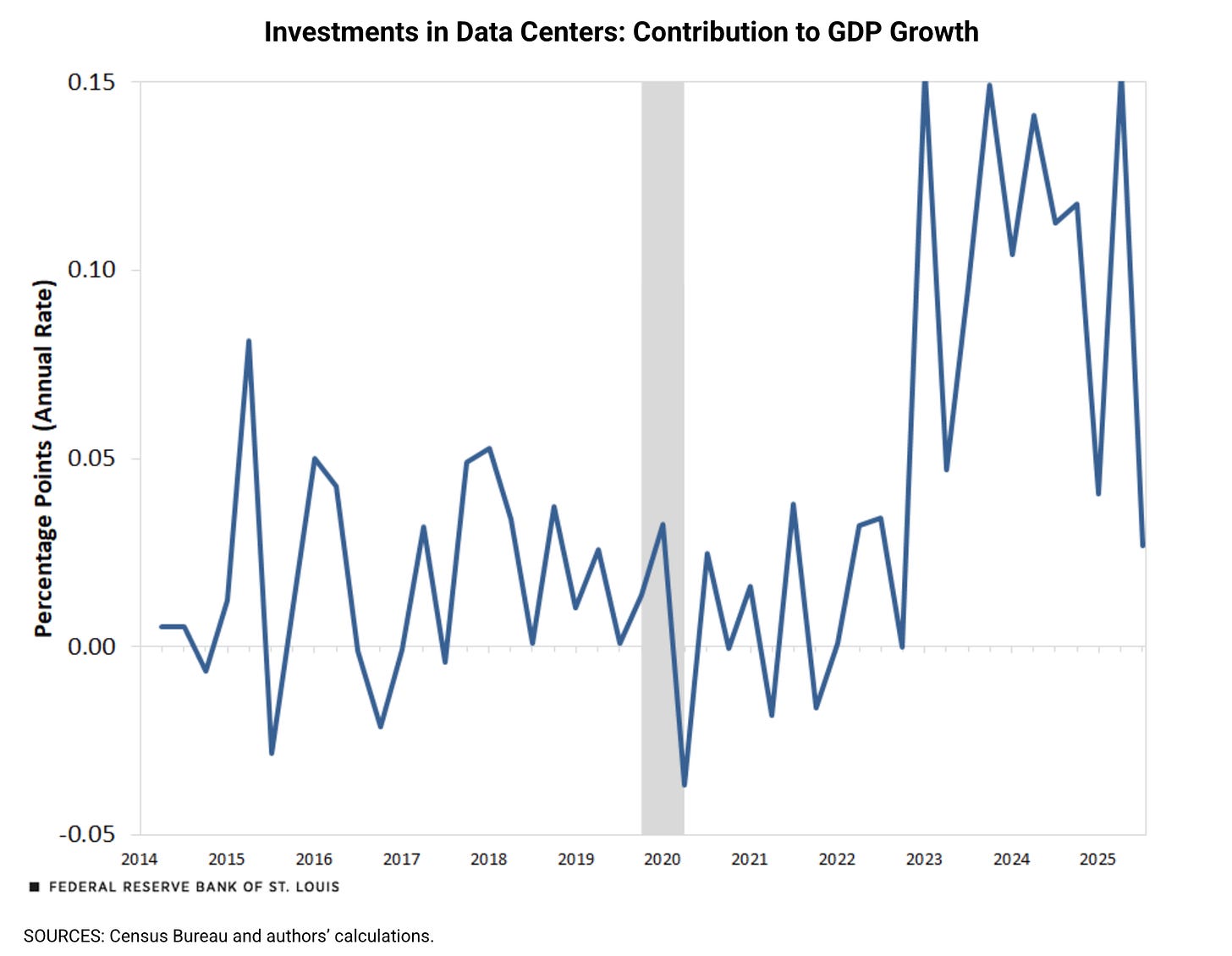

One reason to suspect that the present capex boom in compute is starting to bite into the competitiveness of US manufacturing and tradables is the rising cost of electricity, an essential input into every industry. Industrial electricity costs have increased by about a quarter over the past few years. The compute capex boom is doing to US manufacturing what our blowing up NS2 and the Russia war did to German manufacturing.

And electricity is just the tip of the iceberg. In an important intervention, Warwick Powell describes the unfolding logic of this instance of the Generalized Dutch Disease.

The U.S. lacks the skilled workforce required for a massive build-out of firm generation, or for manufacturing in general. Nuclear welders, pipefitters, specialised civil engineers, and high-voltage linemen are already in short supply. Large-scale construction projects across sectors - from semiconductors to transport infrastructure - are competing for the same scarce pool of skilled labour.

This creates what economists call a “Dutch Disease” effect within the domestic economy: a boom in one sector (energy infrastructure for AI and reindustrialisation) drives up wages and costs, siphoning resources away from other productive activities. Regions that do not see significant energy upgrades will face the worst of both worlds - higher prices for electricity and labour, but no direct investment benefits. This distortionary effect makes national reindustrialisation even harder, as it fragments the economy into “energy haves” and “have-nots.”

Warwick Powell, The 100 GW Mirage.

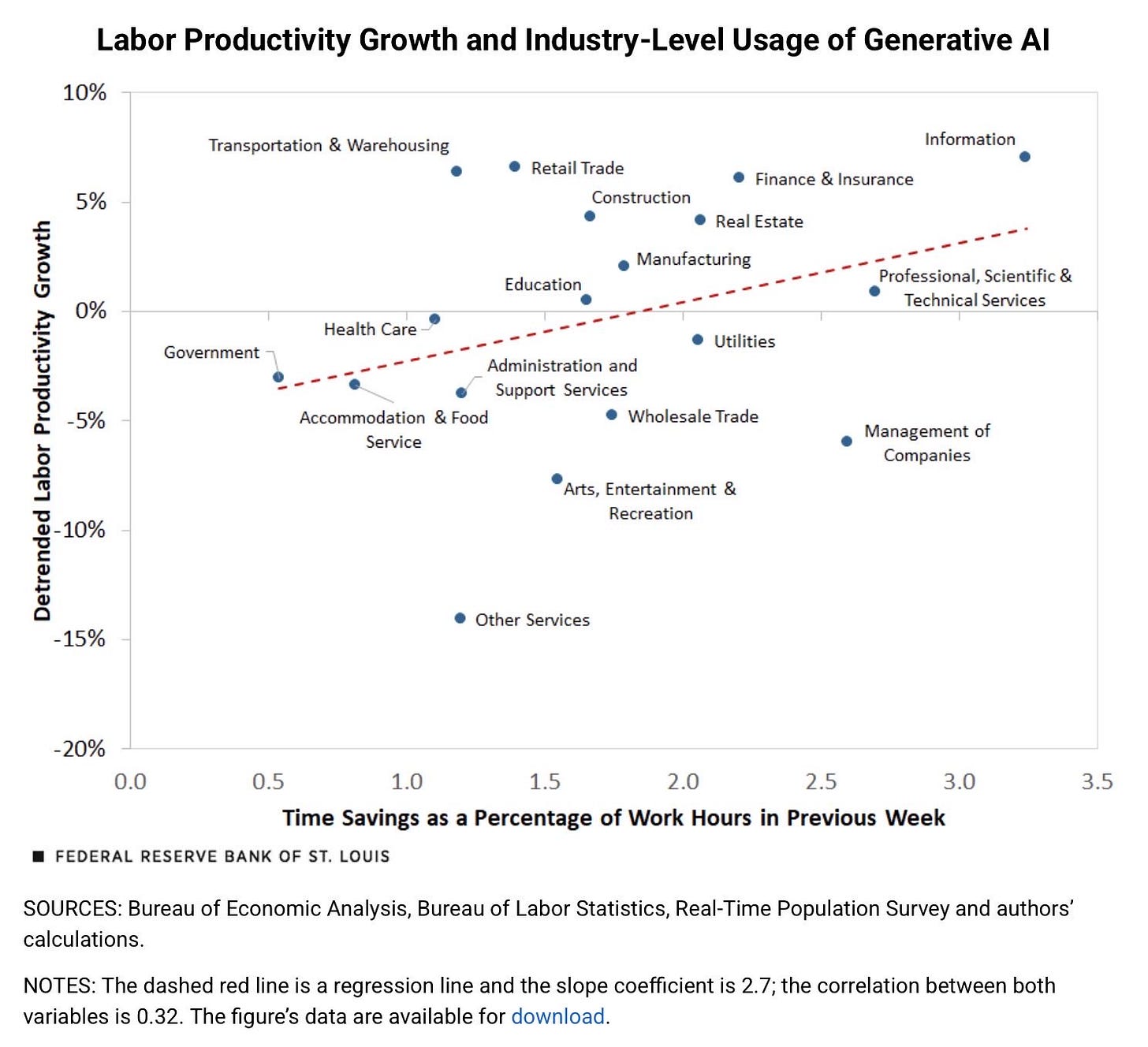

All of this is not to say that the AI boom is a bad idea. The net effect is likely quite positive. Indeed, productivity gains from AI are already visible in the cross-section of industries.

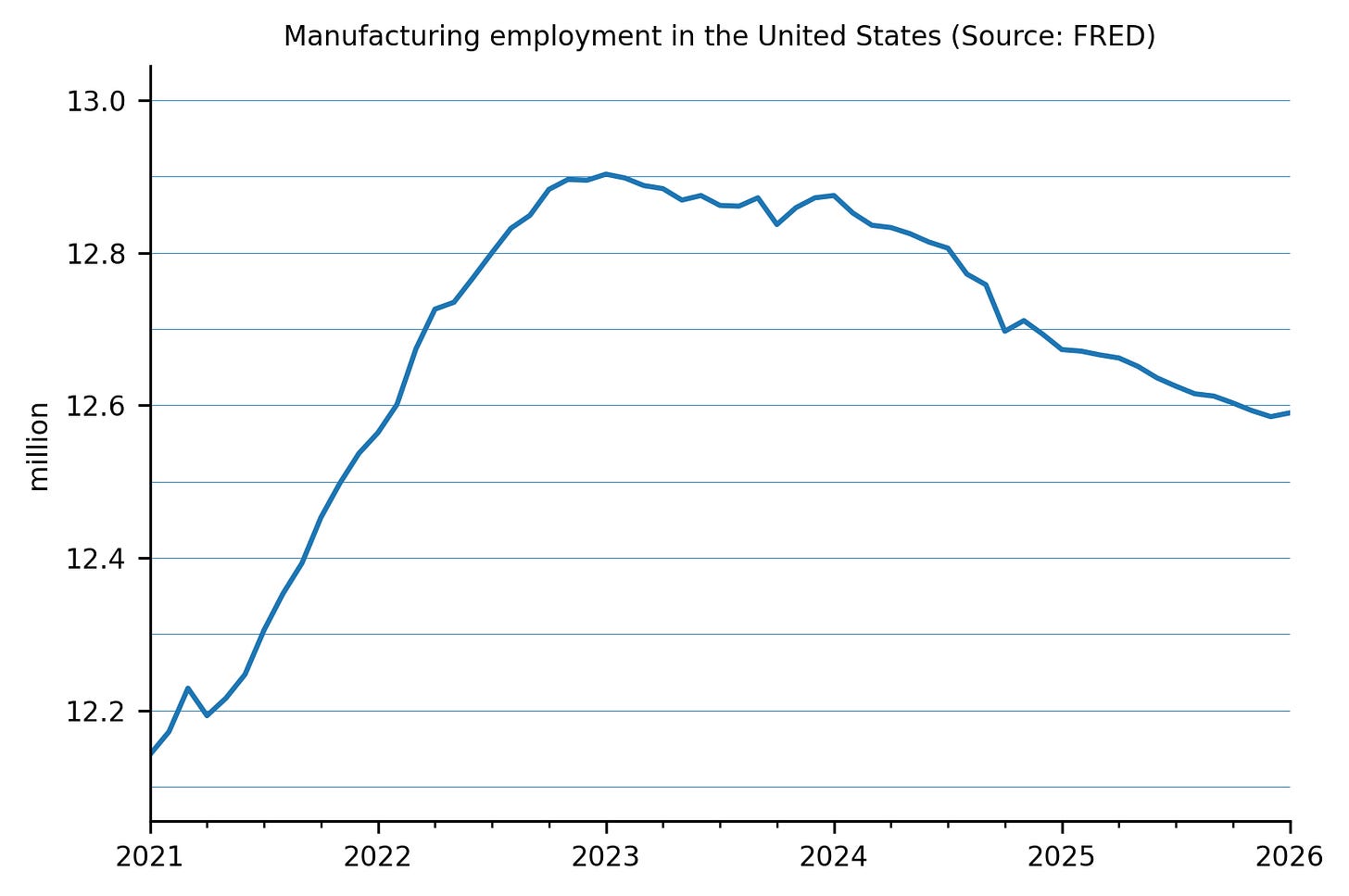

The point is not that AI is bad for the US economy. The point is that it may very well be bad for US manufacturing in particular and the tradables sector in general. More suggestive evidence comes from the timing of the present decline in US manufacturing employment. The decline begins precisely as the compute capex boom takes off in 2023.

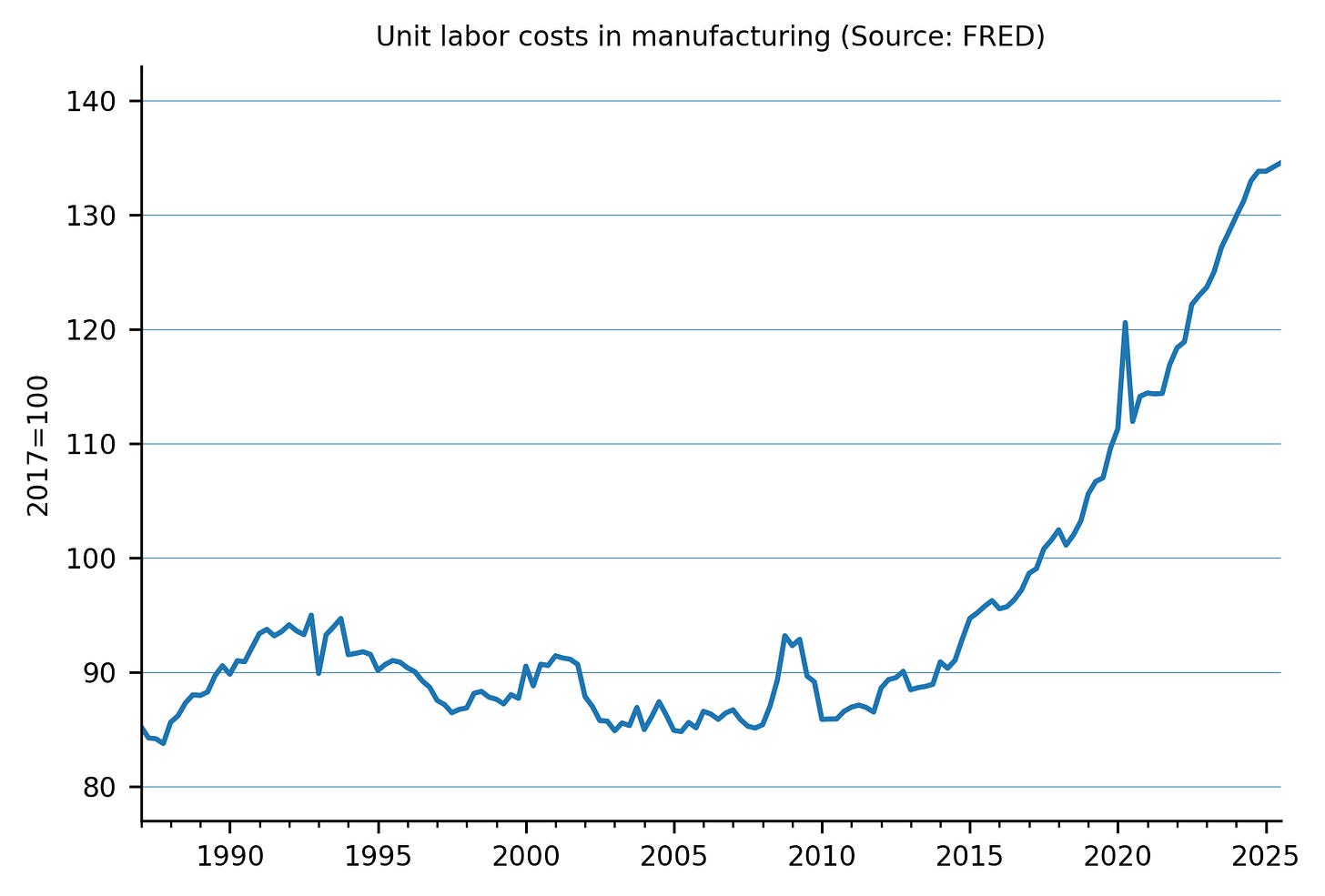

US manufacturing is getting uncompetitive for many reasons beyond the compute boom. Unit labor costs, the principal measure of the competitiveness of US manufacturing, have been going up since 2015. Since then they’ve risen by 42 percent.

Economists love to point out that booms can be productive. That’s true. But they hardly costless, even before we add in the costs associated with the inevitable busts. One cost of these, as we have shown, is that they make US manufacturing uncompetitive. The AI boom, and the tech boom in general, may very well come at the price of further deindustrialization.