Matthew Yglesias recently tried his hand at debunking Case and Deaton’s work on rising deaths of despair—deaths due to alcohol poisoning, drug overdose, and suicide. At first, I was dismissive on Twitter, but Eric Levitz pushed back enough for me to pay attention to the argument. Specifically, Levitz is convinced that the despair is confined to high school dropouts. Because Case and Deaton combine <HS and HS, the charge is that their result overstates the despair of the US working-class. In what follows, I will show that this sanguine assessment—“… it is actually an acute crisis of mortality among the bottom 10 percent.”—is wrong. Despair is not confined to high-school dropouts.

Mortality rates contain a very strong signal of the well-being of a populace. Recall that this is precisely the signal that allowed Emmanuel Todd, unlike all of Western intelligence, to predict the collapse of the Soviet Union. For mortality to rise in an advanced economy is even more alarming.

Apart from the divergence from previous trends, the despair signal can be recovered from the class gap in mortality rates. We need to pay attention to the trend in class gap instead of prevailing levels, because mortality rates have been falling across the advanced industrial world, so the levels at any given point in time are bound to be confounded by (1) the common trend component, and (2) long-standing gaps between the more and less educated that have nothing to do with despair.

If the class gap is widening on the other hand—ie, the college-educated are seeing continuing gains, while the lower classes fall further and further behind—that is a compelling signal of despair and good cause for alarm. Now Case and Deaton have already shown that (1) the diploma divide in mortality has been rising sharply, and (2) the gap between the college-educated and those with some college (and not just <=HS) is widening as well.

However, they do not distinguish between <HS and HS, and therefore do not address the specific issue highlighted by Levitz: “… it is actually an acute crisis of mortality of the bottom 10%.”

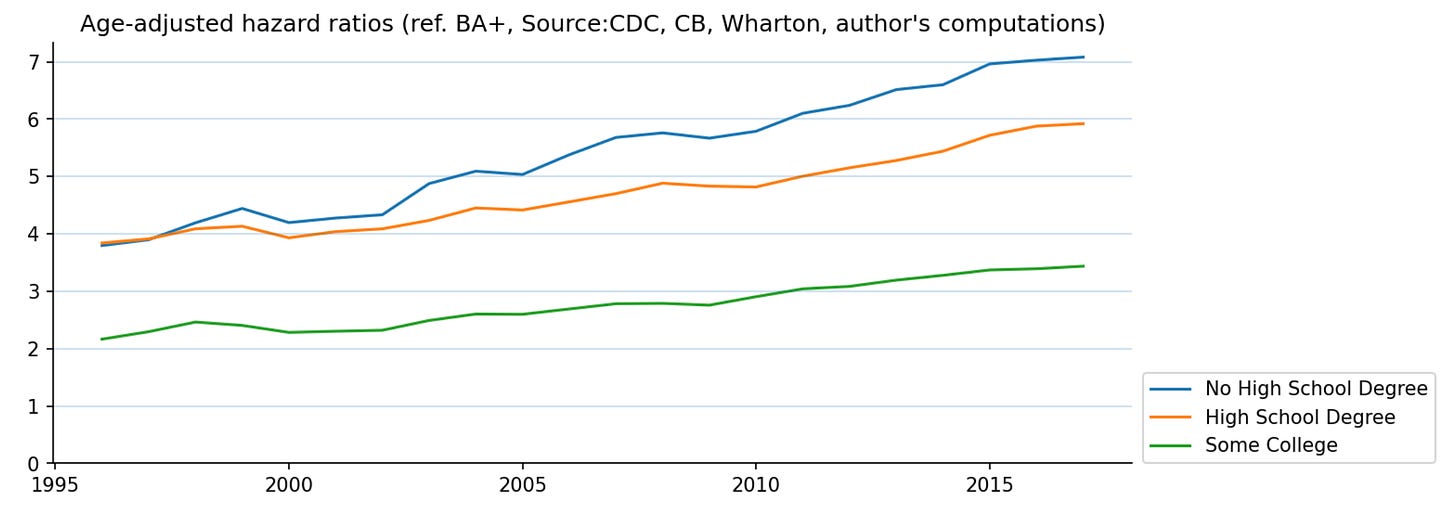

This is an empirical question. We attack this problem using CDC data collated by Wharton. They have age-specific mortality rates by educational attainment. The ordinal categories are <HS, HS, Some College, and BA+. We restrict our attention to 55-69 year olds. We estimate hazard ratios—the ratio of all-cause mortality rates of the educational attainment classes to the rate for college graduates. Here’s what the graph looks like for 60-year-olds.

In order to obtain a more representative graph, we use age-specific population weights to combine age-specific hazard ratios. The next graph displays the population-weighted average of hazard ratios for our age-specific cohorts. By construction, this weighted average of hazard ratios is not confounded by any increase in average age within discrete age brackets. And, as explained above, because we’re looking at hazard ratios, it is also not confounded by the common component. This is as kosher as it gets in this business.

We can see that the upward trend in hazard ratios is not confined to high-school dropouts. It is true that the trend is most pronounced for them. But the upward trend is also significant for high-school graduates and those with some college under their belt. The all-cause hazard ratio has increased by 3.28 for high-school dropouts, 2.08 for high school graduates, and 1.27 for those with some college. The upshot is that, on the wrong side of the diploma divide, despair goes very far up indeed.

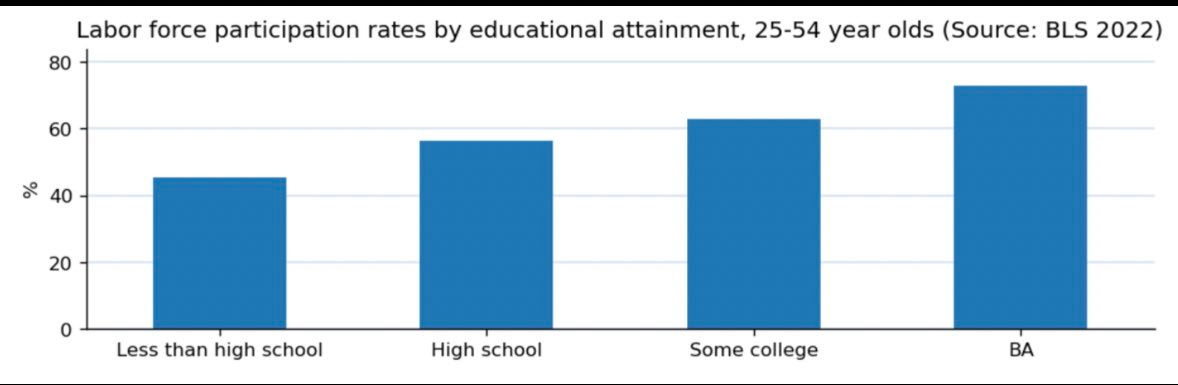

All-cause mortality has a very strong signal. But the evidence for American working class despair is not confined to mortality. Prime-age labor force participation contains the same signal of despair: four out of every nine Americans with only a high-school diploma are not even looking for a job. It’s not like high-school graduates can survive on one pay-check! These are obviously discouraged workers in despair.

Take family reproduction—perhaps the most important factor in human well-being. Following the Sixties revolution in behavioral norms, the rate of family reproduction stabilized for college graduates by the 1990s. But it has continued to fall for high school graduates. See my note from three years ago. And if you’re interested a deeper dive, see Andrew Cherlin’s work.

Or, take divorce rates. For college graduates, 29.7 percent of first marriages end in divorce by age 46. For high-school graduates, 48.2 percent of first marriages end in divorce. (The table’s from here.)

We can keep going. The truth is that American working-class despair is such a robust, large-scale pattern that one can recover the signal from practically anything we care to measure—mortality, morbidity, BMI, labor force participation, marriage rates, child-out-of-wedlock rates, you name it. So, I stand by my challenge to Matthew Yglesias.

Nice to see a solid, fact based treatment of this question. Your rebuttal of Iglesias is convincing.

Anecdote: In the Los Angeles of the 1950s and 1960s, average young couples would move the California and optimistically start a family. Natives too.

When I say "average" I mean it. In my neighborhood of Altadena, my friend's dads were furniture upholsterers, security guards, KFC employee (manager?), construction workers, small college professor, salesmen. In general, they owned houses. When wives worked, it was in the pink-collar ghetto, and often only seasonally, as to buy holiday presents.

"Today, the median listing home price in Los Angeles, CA was $1.2M, trending up 22.5% year-over-year. "

So....the ability to buy a house, and have a decent-paying job, be respected by a wife for the ability to provide---that's all gone for the average guy along the entire West Coast. Much of the Northeast too, I would guess.

I get it, that median incomes per capita are higher now than in the 1960s. Something is screwy with that perspective. Wages for young men, adjusted for inflation, are lower than in the 1960s.

Canada is facing a similar demographic wreck.

Globalism?