Debunking the Pettis-Miran Hypotheses

And how did we get here?

The short term economic outlook is shrouded in uncertainty, but it is not looking good. The economic policy uncertainty index has never been higher. The variance of outcomes remains very large. The impact of policy uncertainty on business is well understood. Firms tend to delay investment and hiring decisions or forgo them altogether, exacerbating the direct impact of supply chain disruptions and higher cost of making things. The main driver is, of course, Trump’s tariff war on the whole world; above all, China.

The medium term outlook is less uncertain. Inflation will rise. The Fed will have to pause on its rate cutting plans, if indeed not hike from here, depending on how bad the inflation gets, and especially on whether inflation expectations threaten to get deanchored. In this regard, the University of Michigan’s February survey showed that consumers were already expecting headline inflation to rise to 6.7% over the next twelve months. Uncertainty regarding inflation had also risen, with the interquartile range of responses rising from 5.5 in December to 9.5 in February. It is unclear how large a jump we will see in consumer inflation expectations. But it is likely to be very large. So, we may very well be looking at multiple hikes, with the policy rate rising perhaps to well over 5%, depending on the scale of the shock and how much expectations get destabilized. This is turn, together with the direct economic impact of the stupidity shock, implies a very real risk of recession. Goldman has scaled back its recession probability from 100% to 50%. But a serious slowdown of the economic is virtually guaranteed at this point.

The longer term outlook is much less uncertain. The United States will be poorer and weaker. American firms will be less competitive in global markets and will see their market shares erode world wide. Americans are going to see their real incomes fall, perhaps dramatically—depending on how late in the day the White House capitulates. Suffering will be most pronounced for the American working class, with real incomes of median earners perhaps falling as much as 10%. The GOP will pay a stiff price for Trump’s idiotic quest to remake the global economic order and extract tribute from every nation on earth. Even if he backs down completely, much of the damage to the economy and the GOP is already baked in at this point.

The entire American world position has been shattered by monkeys fiddling with the knobs in the cockpit. There is virtually no possibility anymore of resurrecting Bridge Colby’s ‘counter-hegemonic coalition’ in Asia, or the global anti-China coalition that Biden’s cold warriors had marshaled with great effort and considerable kicking and screaming by America’s former partners and allies. Even if Trump does not reimpose any of the tariffs he has paused, countries like Vietnam, Indonesia, Malaysia, South Korea and perhaps even Taiwan and Japan, understand that the US cannot be relied upon and therefore they must come to terms with China.

Europeans had already learned from Vice President Vance’s lecture at Munich that they cannot rely on the Americans, and must immediately make arrangements for their own security. The Trump-Miran idea of extracting tribute from the whole world has alarmed them even more. There is now no scenario in which Europe does not attain strategic autonomy and regards the US at best warily, leaving the United States diplomatically isolated, and its influence in the world reduced dramatically. And they are already making a beeline for Beijing, as they must. The Spanish prime minister, the French president, and the leaders of the European Union are all begging for a face-to-face meeting with Xi, the newly-minted leader of the anti-American world order.

Trump has even managed to make an enemy of the one power that we should never, ever have broken relations with, because a hostile state on our border poses a long-term security threat to the American homeland. His tariff war, threats and harassment have stiffened Canadian spines, and dramatically shifted the political balance in the country. Mark Carney, who has made it absolutely clear that he will stand up to the bullying and work with other powers against the United States, is set to win a resounding victory against Trump-sympathizing Conservatives. Expect Carney to beat Macron in getting an audience with Xi.

So, the Trump administration’s harebrained attempt to reorder the global economic order and bully everyone into submission has been an unambiguous catastrophe for the American people, for American firms, and for America’s world position. Maybe something can be salvaged come 2029. But the world by then will look very, very different from 2024. Maybe US economic health can be restored with the return of sanity. But the American world position can no longer be salvaged. They have wrecked it irrevocably because no power on earth can bank on the idea that Trumpism will be contained even after the electoral backlash that is assuredly coming. Therefore, they must make alternate plans for their security and well-being; plans that exclude dependence on the United States. And this must necessarily mean enhanced cooperation and good relations with China. We have lost the long-term strategic competition already. The United States has committed geopolitical suicide.

How exactly did it come to this? How did we get here? As I have argued many times before, there is a very simple recipe for any policy-induced catastrophe: you think the world is a certain way, but it is not so, and grand schemes based on misperceptions of world lead you straight into the ditch. In Vietnam, American elites thought that they could break the will of the adversary through violence; not appreciating the price that the adversary was willing to pay to prevail and the attendant unfavorable balance of resolve. This directly led to the collapse of the midcentury order at home and military humiliation in Asia.

Or take a more recent instance. The Biden team, in retrospect, a paragon of competence, believed wrongly that clever tactical suppression of Chinese technological progress could arrest the growth of Chinese power. The chips escalation that emerged from this misunderstanding led instead to an acceleration of Chinese technological progress, not just in chips and AI, but in their whole tech-industrial ecosystem.

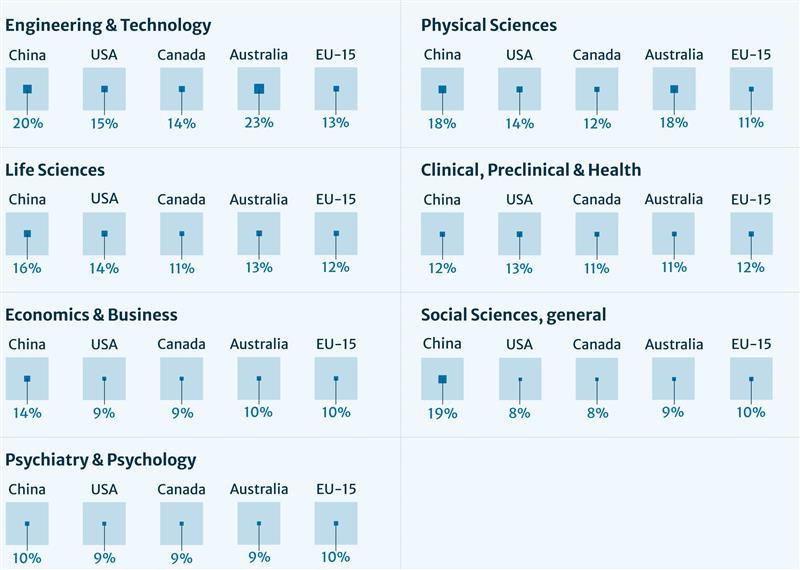

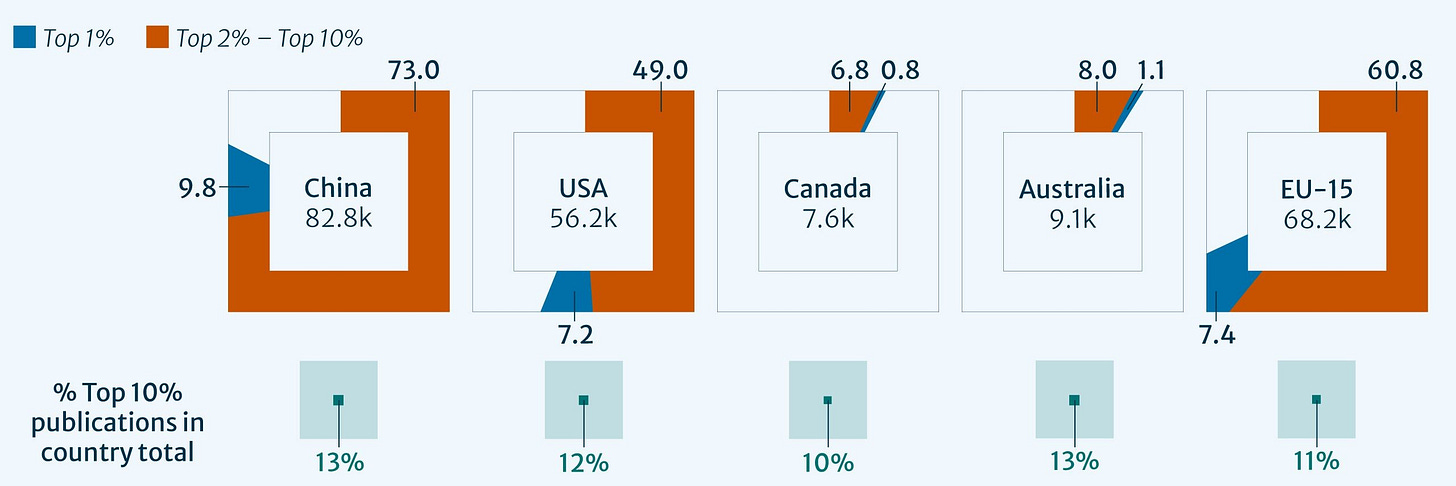

The Jake-Schmidt stratagem backfired spectacularly because it was based on an incorrect assessment of the conditioners of technical progress. The main conditioner was not access to TSMC chips; it was the sheer scale of human capital at China’s disposal, and the will, the strategic vision and the competence of the Chinese government. Recall that China practically leads the world in average cognitive ability, and it has more STEM graduates than the US has graduates of all stripes; it’s STEM PhD production is already much higher; and it’s high-quality research output by now surpasses that of the United States. Chinese advantage is especially pronounced in engineering and technology, and the physical sciences—the fields most relevant to the balance of power.

In order to comprehend the scale of the challenge posed by the rise of China, examine the above graphs very carefully. Once you digest these brute facts, it becomes completely obvious that (a) clever tactical stratagems like the chips escalation cannot possibly yield any lasting advantage; (b) hard decoupling—even if Europe were to join the US, which is no longer a possibility—cannot arrest the growth of Chinese power; and above all, (c) we have a narrow window to reach a long-term modus vivendi with China before the last American advantage—in hard military power—also vanishes and China unambiguously gains the upper hand in every relevant domain of power sensu Wohlforth (1999). But this is not a note on China. On my recommendations for US China policy, see my essay from last year.

Like the Vietnam war and the chips escalation, the catastrophe of the Trump revolution in US world policy is also based on a misperception of the world; an incorrect understanding of the American interest and of the American world position; a fetishization of a second order correction term with absolutely no bearing on the American world position or the welfare of the American people: the fucking trade balance.

The thesis, most cogently argued by Michael Pettis, is that countries with high savings and attendant trade surpluses hog manufacturing—they are able to secure a larger share of the world’s manufacturing output, value-added and employment. Conversely, countries that have low savings and attendant trade deficits pay the price for the perfidy of the high savings nations in terms of a lower share of global manufacturing. What is truly mind-boggling about this thesis is that it is so easily debunked. No serious economist buys it. The only people peddling it are fake economists who have not published a single paper in an economics journal, ever.

We will first debunk the thesis and its variants in detail. And then turn to the more important question of how it came to be that these fake economists occupied such commanding heights in our public sphere. That is, what has gone wrong with the production of public truth claims in the United States? This is a question of great import because, even after the demolition of the American world position, we still have to manage national decline; there is still a country to run; national problems to be fixed, above all, the suffering of the American working class. The welfare of the American people will need to be secured with good policy as long as we continue to exist as a nation and long after the eclipse of American world power. All of these are jeopardized by the malfunctioning of our system of the production and validation of claims about the world and how it works.

Pettis’s argument is usually evidence free. But on the pages of Phenomenal World, he did offer some. Specifically, he presented this graph.

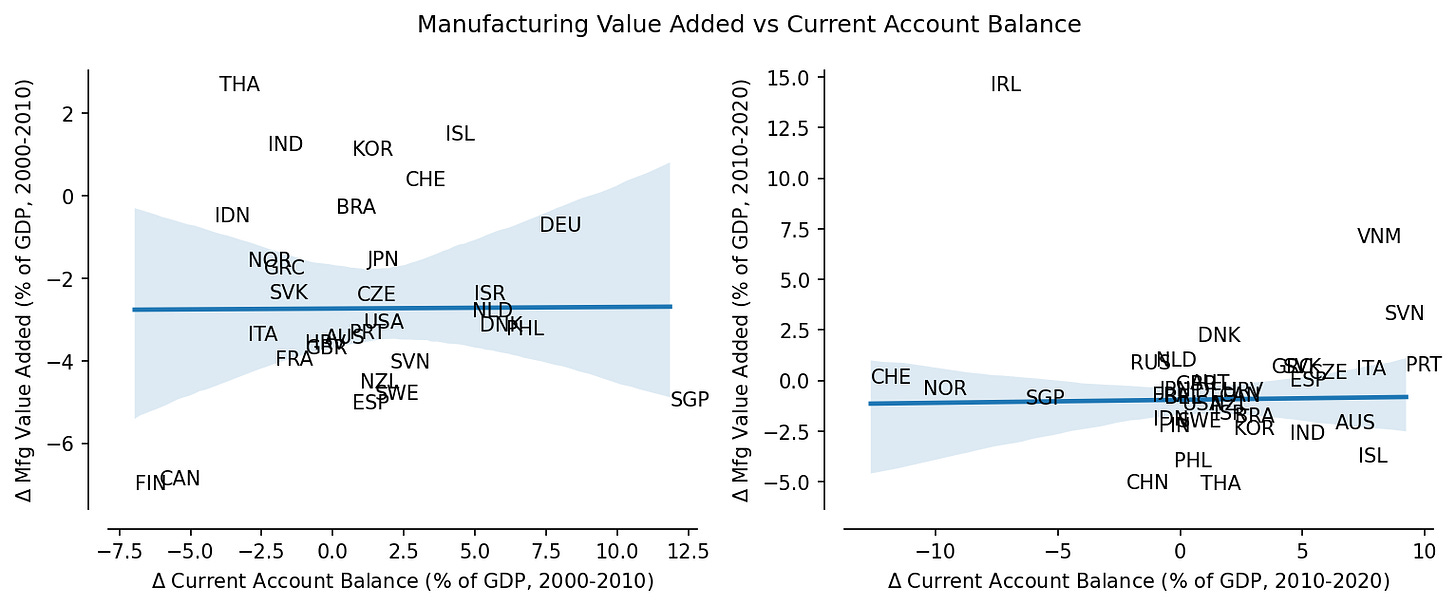

There are two elementary statistical issues with this graph. First, he’s just cherry picking ten countries, calling them “ten largest advanced economies.” That’s incorrect. The Netherlands has a larger GDP ($1,150bn) than Switzerland ($885bn). But regardless of this minor mistake, there is no reason why the evidence from the ten largest AEs should be compelling. Instead of cherry picking, he should’ve examined the evidence from all industrial countries, especially Asian countries that have industrialized the fastest in the past few decades. There may be a case for restricting the sample to AEs. I’ll show you the evidence for both.

The other issue is much more serious. It is extremely well-understood that levels are confounded by country specific factors. In order to argue that current account imbalances drive manufacturing share, at the minimum you need to look at changes in both variables, rather than their levels. This is really elementary; so elementary, in fact, that it is taught in freshman statistics. This is really not up for debate. You have to detrend. You should also control for other possible confounders. But this is compulsory.

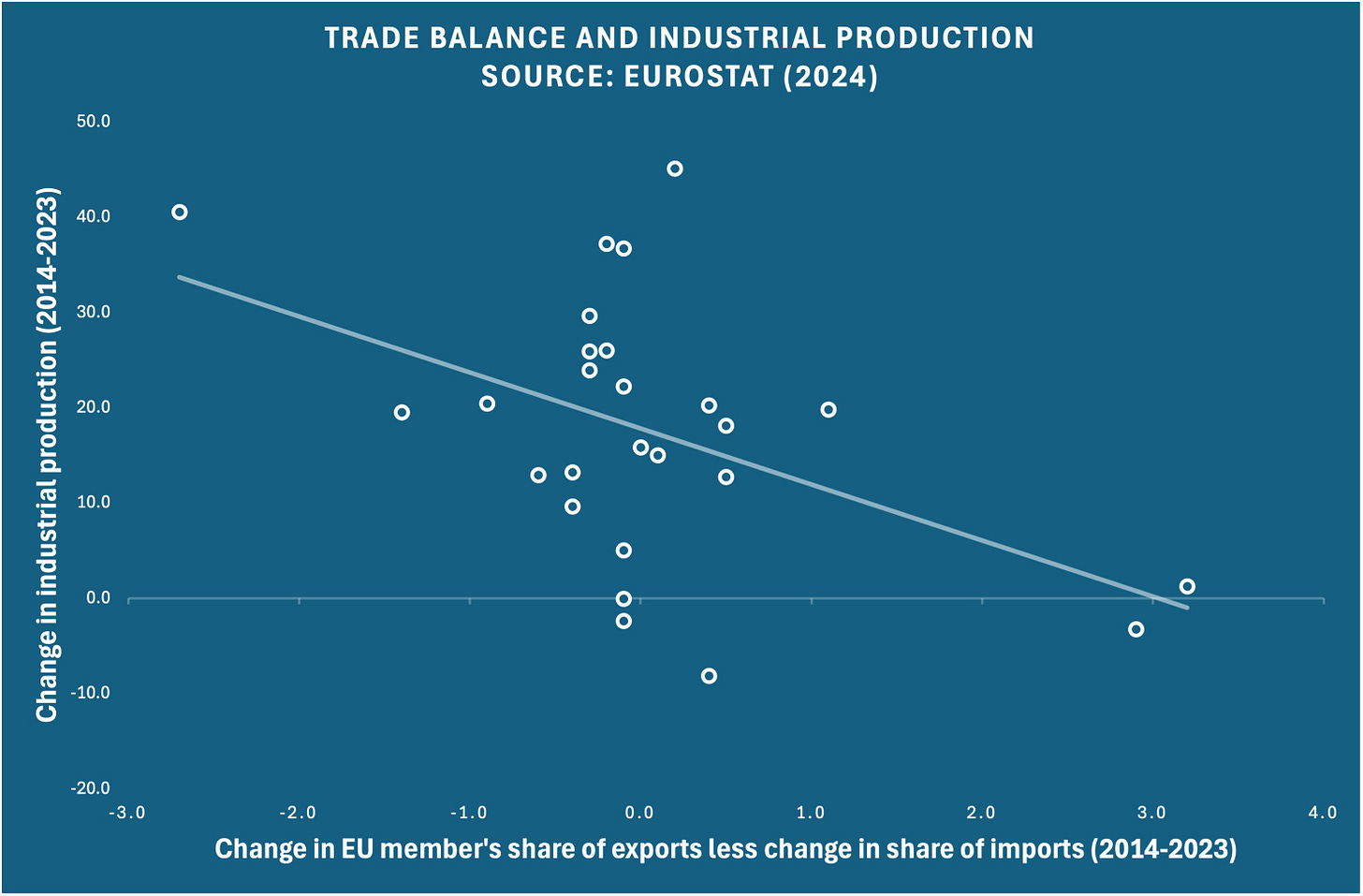

The other main confounder is exchange rates. Surpluses tend to appreciate currencies at the margin, which tends to reduce your share of world manufacturing since your producers become less competitive on the world market for tradables (all manufactured goods are tradable sensu Hlatshwayo and Spence, 2014). This obviously confounds the direct effect of surpluses on manufacturing value-added, although not the total effect. One tightly controlled sample that is robust to this issue is the eurozone. This is why I originally tested the Pettis hypothesis with data from the eurozone. The relationship turns out to be precisely the opposite of that predicted by his hypothesis—that higher surpluses imply higher shares of industrial production. We find instead that the relationship is negative.

Now let me show you the full sample. I throw out non-industrial countries and micro-states. My sample includes all participants of any significance in the global manufacturing game. Here’s the full list of 37 countries.

['Australia', 'Austria', 'Belgium', 'Brazil', 'Canada', 'China', 'Croatia', 'Czechia', 'Denmark', 'Finland', 'France', 'Germany', 'Greece', 'Iceland', 'India', 'Indonesia', 'Ireland', 'Israel', 'Italy', 'Japan', 'Korea, Rep.', 'Netherlands', 'New Zealand', 'Norway', 'Philippines', 'Portugal', 'Russian Federation', 'Singapore', 'Slovak Republic', 'Slovenia', 'Spain', 'Sweden', 'Switzerland', 'Thailand', 'United Kingdom', 'United States', 'Viet Nam']

We look at changes over two decades, 2000-2010 and 2010-2020. We find that there is no gradient at all. It is simply not the case that higher current account surpluses imply higher shares of manufacturing value added. Ask any serious economist or statistician: this is dispositive refutation of the Pettis hypothesis. The relationship that the Pettis hypothesis implies simply does not exist in the data.

The Miran “American exceptionalism” variant of the Pettis hypothesis relies on the idea that the dollar is the premier safe asset of the world economy, so that—presumably because of a global shortage of safe assets, see Caballero, 2006, 2014, 2017—(1) the dollar is persistently overvalued, so that (2) the US runs a persistent deficit, which has (3) ‘decimated’ US manufacturing. The safe asset shortage may no longer be true after the extraordinary issuance of AE debt since the Covid shock. (1) is simply false, as I will show. (2) is, of course, correct, but that does not imply (3), as Miran claims, and I demonstrate below.

On the financial side, the [1] reserve function of the dollar has caused persistent currency distortions and contributed, along with other countries’ unfair barriers to trade, [2] to unsustainable trade deficits. These [3] trade deficits have decimated our manufacturing sector and many working-class families and their communities, to facilitate non-Americans trading with each other.

Stephen Miran. White House. April 7, 2025. Numbers in brackets are mine.

Let’s take these in turn.

(1) Has the dollar been persistently overvalued? No. There has been no persistent overvaluation of the dollar. It has fluctuated quite a lot: weakening in the 1970s, strengthening after the Volcker coup in 1979, weakening after the Plaza Accord in 1985, rising again after the Asian financial crisis, weakening dramatically after 2002, and then rising again after the global financial crisis. In particular, in the crucial period during which the so-called China Shock is supposed to have gutted US manufacturing, 2000-2008, the dollar fell by 13 percentage points! Since the global financial crisis, the US has grown much more strongly than other AEs, so that they have lagged behind the US monetary cycle, which is why the dollar has strengthened over the most recent period. Note also the great anomaly of the Miran hypothesis: the strongest period of American industrial growth was the 1960s, when the dollar was at its historical peak!

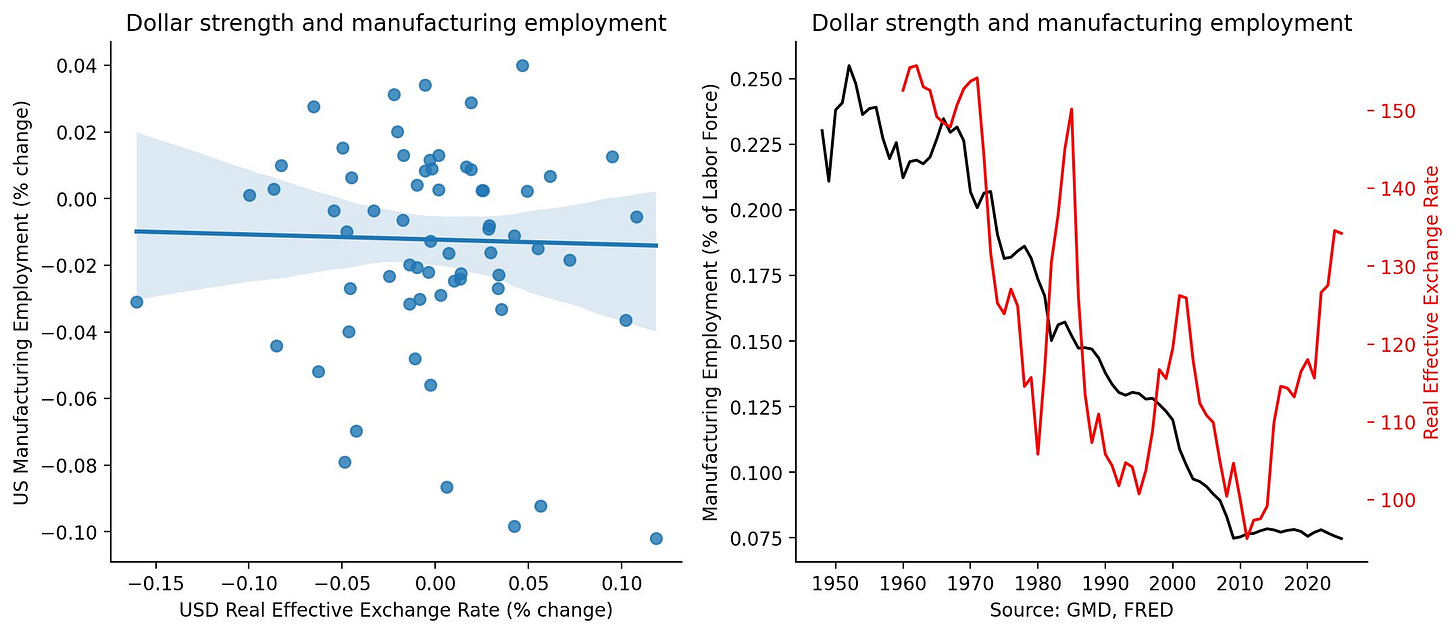

Does (2) imply (3)? Ie, Has dollar strength ‘decimated our manufacturing sector’ as Miran claims? No. Here’s the proof.

If Miran’s claim were true, a mightier dollar would predict a decline in US manufacturing employment (recall that we must necessarily detrend to avoid the common trend component that confounds levels correlation). There is no such relationship. And here’s the great anomaly: precisely when the dollar has gained strength since the GFC, US manufacturing share of employment has stopped falling! There is not a shred of evidence for the claim that dollar strength has decimated US manufacturing in any systematic fashion.

There is an even stronger reason to think that the Miran idea is a total red herring. The reason is that, outside of rapidly industrializing developing nations—China, Vietnam, Thailand, India, and Indonesia—manufacturing employment has declined in every single country in our dataset. It has declined even more in Germany than the US, despite the alleged benefits of ‘the euro being too weak for Germany and too strong for Europe’. And Germany runs the largest current account surplus in the whole goddamn world! In fact, it has declined even more in Japan and South Korea than the US. Has anyone ever accused the Koreans or the Japanese of running deficits or sporting strong currencies? Haha.

What about the folk idea that NAFTA and the so-called China Shock gutted American manufacturing? The graph below is from Kyle Chan. Definitely see his excellent note and references therein. It shows very clearly that neither NAFTA, nor the so-called China Shock had any discernible effect on US manufacturing employment. I have also previously debunked the Autor et al. hypothesis in my China policy note. See especially the references therein.

Look, as I’ve shown you, manufacturing employment has declined across all incumbent industrial nations. Why is it only the American working class that has suffered so? Baldwin suggests that the reason is the lack of a real, Western welfare state. And that is true to a degree, certainly. But I believe there is much more important factors at play; factors specific to our domestic arrangements: the power of finance over industry that has oligopolized industry after industry, central to which is the buyout game whereby private equity moguls use the target firm’s assets as collateral to purchase the firm, and then force it to disgorge all surplus, leaving nothing for long-term investment or job creation—our equities are overvalued for such structural reasons; the total dismantling of labor power; the fortifications of the professionals, the power of corporate lobbies, and the attendant proliferation of rents in the system; and so on and so forth.

Skill-biased technical change happened everywhere: why is the American working class suffering so? Why the hell isn’t the Danish working class suffering from the same hour-glass economy? After all, manufacturing employment has declined even more precipitously in Denmark! Or pretty much anywhere else beyond the US and the UK? That is the question that must guide the search for reform. When we pick up the pieces after.

We have seen that the Pettis-Miran hypotheses are demonstrably not true. Nor are they supported by any serious economist of repute. How then did they gain such extraordinary currency in our public discourse. More generally, how did we get to our present catastrophe?

How did Stephen Miran, a strategist at a hedge fund, whose sole contribution has been a note to investors that strategized how tribute could be better extracted from US protectorates, become the chief economic advisor to the president? Was it not because his note was pumped up by Gillian Tett and others at the FT and beyond? Did Trump even know of his existence before?

How did the ideas peddled by Michael Pettis and Matt Klein become mainstream, despite being known to be empirically challenged? Was it not because of the extraordinary acreage afforded to him in our prestige media?

How did Brad Sester, who has not proven a single claim in his entire professional career become so influential? Why did Adam Tooze, a former historian who has since emerged as a Davos whisperer and general purpose intellectual—a man who was afraid enough of me to ask me not to show up for the seminar where he discussed the global financial crisis, because I was the one who taught him how finance actually worked and might prove embarrassing given that I am not afraid to correct anyone in public—champion this fake economist and others like him?

How did these fake economists—all of them, without exception—gain influence in America and lay the basis for the American suicide? What happened to the real economists? Did we run out of them? Contrary the bullshit peddled on at the Verso Loft, we did not run out of serious economic thinkers; nor is economics in crisis. It is, in fact, in great health. What happened is that our media elite started pretending that idea men perched at think tanks and so on were the intellectual equals of actual economists who have made real contributions to the economic literature.

Stephen Miran has not published a single paper in any journal, forget about the big five. I have more publications than him. Brad Sester has not published a single paper in an economics journal either. Same goes for Matthew Klein, who is a good number cruncher, but hardly an actual economist since he has contributed zero papers to the economics literature. How many has Michael Pettis published? Zero. How many has Adam Tooze published in anything outside history? Zero.

These are all fake economists in a strict sense and demonstrably so, by any criterion of professional expertise. Why has the media been pretending for years now that these are real economists? That their ideas are to be taken seriously? Because a major part of the reason why have landed in the soup we have is because we have lost track of how to tell bullshit from real thing in our public discourse.

The reasons for their celebrity is not hard to discern. First, they are saying things that make good copy—just like Trump made for good TV in 2015. Second, what they are saying often aligns with the agenda of the powerful. After all, this fraud was perpetuated on the American people long before the present administration. In particular, with the entire American media-political elite signed up for a Cold War against China, some major crime of the Chinese had to be seized upon. Everything was tried. From inflated claims about Uyghur enslavement, to pumped up charges of technological theft, spy balloons, Chinese students and scholars, and so on and so forth, ad nauseam. The one that really stuck was the cooked-up panic over China’s trade surplus and industrial subsidies.

The reason for that is again not hard to discern. It tied neatly to the crisis of the American working class. As Richard Baldwin, a real economist, wrote in a recent LinkedIn post, a scapegoat had to be found. China proved ideal. It dovetailed really nicely with the panic over the growth of Chinese power and the cold war agenda of the Biden mechanics. Whence the New Yellow Peril, and the non-stop attention paid to these fake economists and their fraudulent theory of what has gone wrong at home, and who and what caused insults to the American working class.

Media elites did not foresee the consequences of platforming the fake economists—without providing so much as a single Op-Ed by a real economist to contest the fraudulent claims being peddled. This is proven to be extraordinarily costly. It has cost us our entire world position. This has to stop.

We rely on a very specific arrangement of the production and validation of public truth claims in the United States: we have half a dozen agenda-setting papers: FT, WSJ, NYTimes, WashPost, Bloomberg, and Foreign Affairs. The rest of the media pick up the agenda from there. There are other serious publications like the London Review and so on. But they are not part of the system of regulating our public sphere. For the most part they are ignored.

In effect, we have a small oligopoly that regulates what is platformed for national policy discussion. This endows the editors and scribes at these papers with extraordinary power. But with extraordinary power comes extraordinary responsibility. Look at where you have gotten us by going along with all this bullshit! If we are to pick up the pieces and make a serious go at reform, this has to stop. I am not asking you to platform me, nor necessarily de-platform Pettis, Sester or Cass. But what you absolutely must begin to do immediately is platform serious people, above all, actual economists; and set a much higher standard of evidence than has hitherto been the case. More generally, our present crisis should make you think real hard about the practices in your industry and how they relate the production of truth claims in our media-political system. The elite media not just any industry. It is a crucial component of our system as a whole. We cannot even hope to pick up the pieces without a drastic change in media practice and a revival of journalistic integrity. Our system of production of public truth claims is utterly broken. That is a big reason why we have landed in the soup we’re in. Fix it.

Thank you so much for naming those fake economists, whom I have wished to disappear from the public discourse for so long! I might add two clowns, Pettis and Sester, share something in common: They love to throw around a few accounting identities all the time, mistakenly take them as causalities.

An incredibly important and timely post.

I've been looking for a "one stop shop" for evidence against the claims of Pettis Miran et al. so this is extremely useful, thank you!

The concluding points regarding our media ecosystem is also insightful, it is not emphasised enough the degree to which elite media is the lode bearing weight of our entire system. When it starts pumping out garbage, the risks are massive.

By the way, a point I haven't heard discussed in relation to Miran's arguments that really struck me when I first came across them- they weirdly remind one of Yanis Varoufakis' 2014 "global minotaur" model of net imbalances but with the roles inverted, with the US recast from villain to victim.