The Etiology of American Instability

Why did no one notice?

Once in a while, an off-hand comment made on twitter turns out to be precisely correct in that it unlocks the door to the right line of attack:

[Trump] happened for the same reason it took Case and Deaton 15 years to even notice that working-class Americans were killing themselves in despair.

The question is not only why the American working class family unraveled—even closer to the bone is why it took so long for anyone in the expert class to even notice.

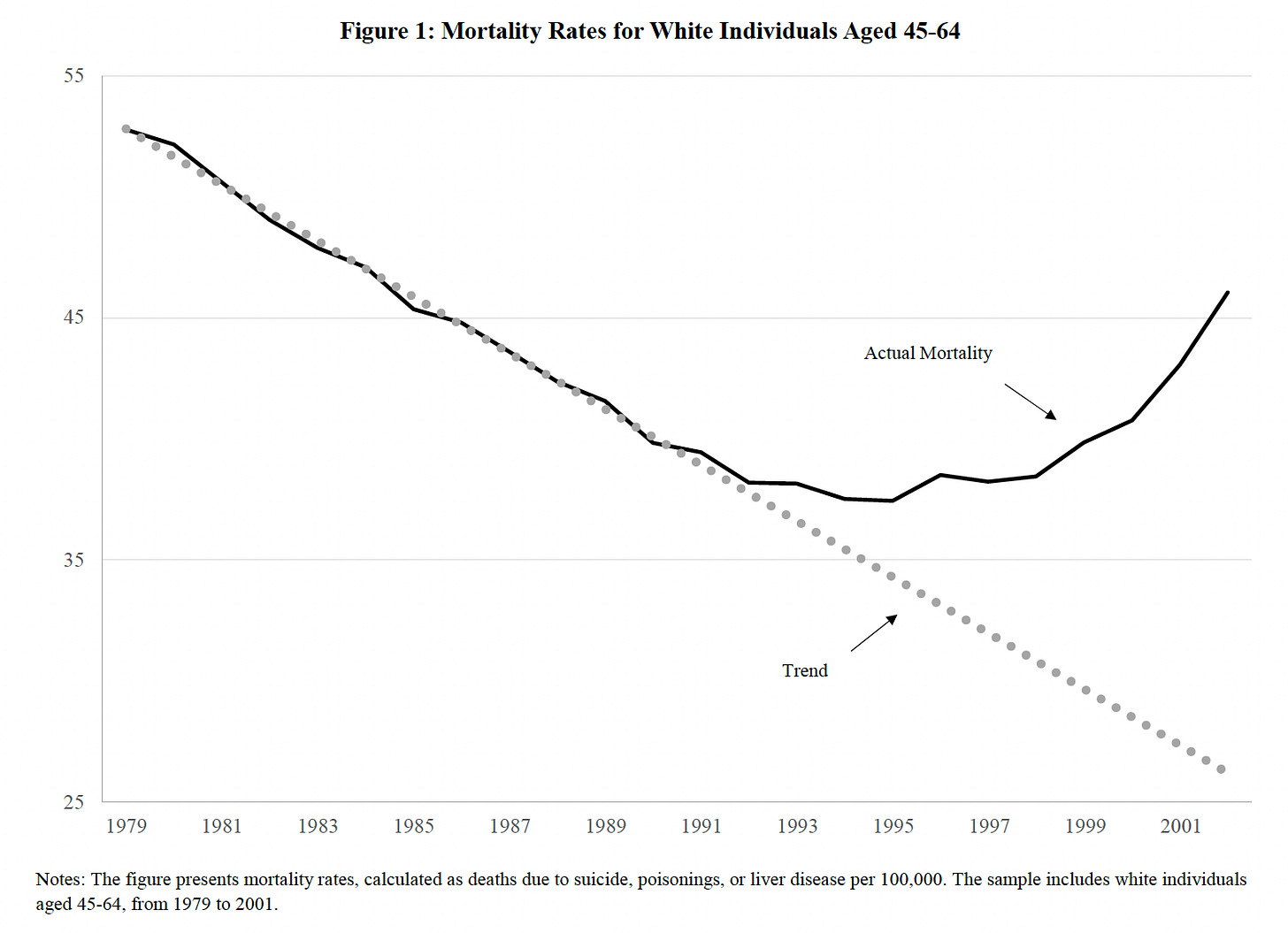

The structural break in mortality and morbidity rates dates to the mid-1990s when President Clinton was throwing parties at the White House to celebrate the New Economy. This is long before the alleged China Shock, ofc, making a mockery of Autor et al.'s import-competition theory of US working class despair.

So, how come no experts flagged the alarming rise in mortality in the late-1990s and early-2000s? One can imagine an alternative universe where an enterprising job market candidate flags the class divergence in mortality already in 1996, gets published in 1997, with the academic hullabaloo getting picked up by the papers in 1998, in turn forcing Congressional inquiries into the matter as the century closes—perhaps followed by reforms that temper the class divergence in well-being.

This is how our open technocratic society is supposed to work. But for twenty years, no expert flagged the alarming pattern. Why?

We’ll return to this question in due course.

In the Democrats’ electoral post-mortems, one finds only degrees of ignorance or dismissals of slow-moving, structural causes. Adam Tooze, reputed to be a historian, offered a self-consciously tactical view on the pages of the London Review of Books.

[W]hat was at stake on 5 November were the 270 seats in the electoral college. And to have a decent chance of winning them, it was not necessary to build a historic progressive bloc. It was necessary to run a competent campaign and to field candidates capable of presenting America’s reality, both its promises and its challenges, in language that was compelling and reassuring at the same time. Biden and Harris both failed to do that, and Biden’s outrageous refusal to step aside until the last moment robbed the party of any chance of finding a stronger candidate. [Emphasis mine.]

I had a nearly violent reaction to reading that. It is one think for a political tactician like Shor or Nate to explain the Dems’ electoral humiliation in these terms. We do and should expect more awareness of historical causation on the pages of the London Review. For the important question is not whether Democratic elites could’ve done something different and squeezed past 270. Maybe they could have. But what does it matter? The real explanandum is not the raw electoral college count in 2024. It is: how can it be that the Democrats need to squeeze past a Trump at all?

The real question, in other words, is how did the United States, as a party-political system, get to a place where a personalized, pluto-populist party can give the party of experts a run for its money.

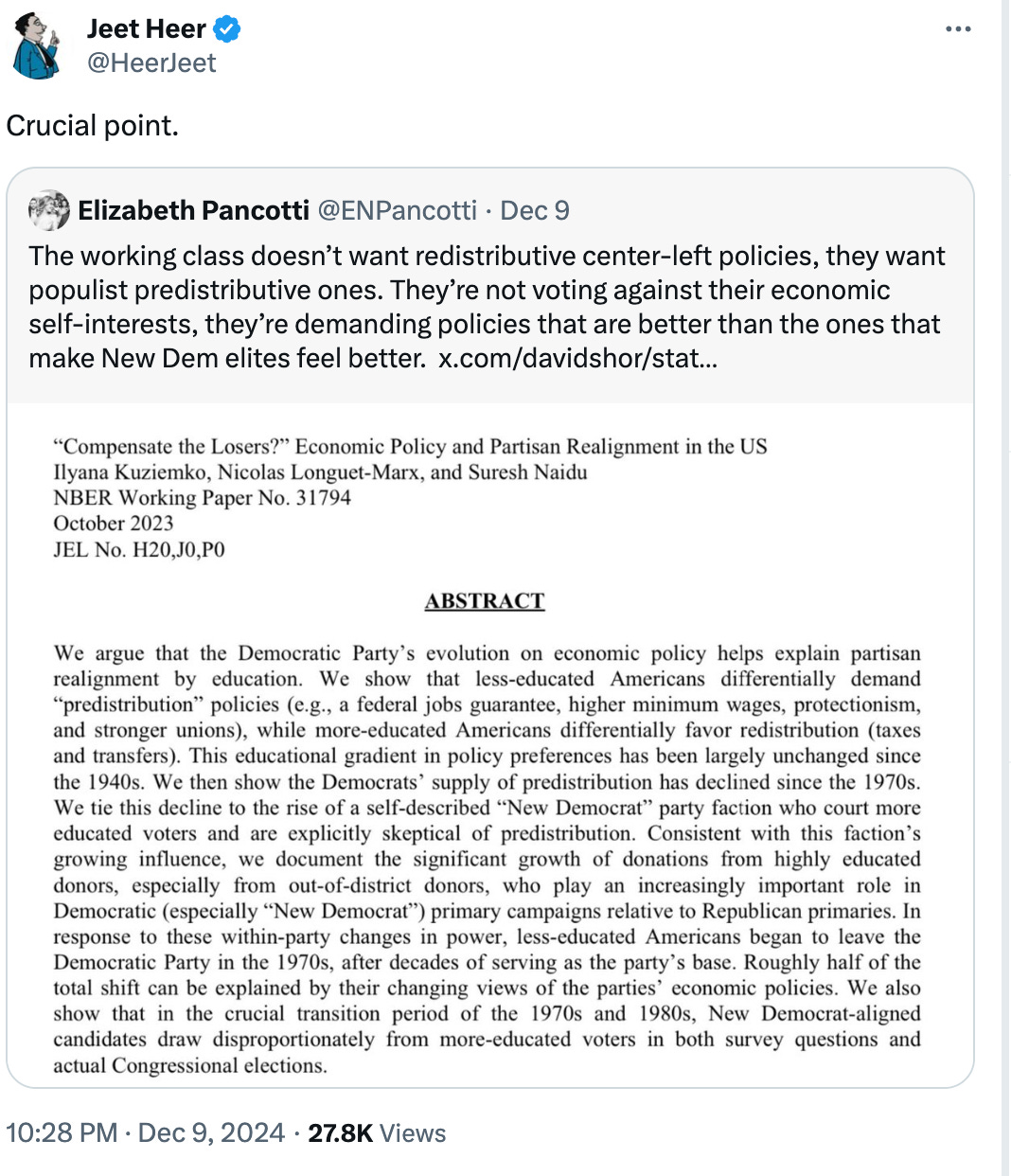

Perhaps Tooze is an outlier. Even a professional tactician like David Shor was open to looking beyond tactics. He noted, for instance, that affluent elites are more in favor of redistributive policies than working-class breadwinners. And that this structural fact has obvious implications for tactics (“political strategy”).

The fundemental coalitional fact of our time is that wealthy voters are more supportive of economic redistribution than the working class right now.

That’s ideologically inconvenient but it’s true and ignoring it just leads to incorrect political strategy.

David Shor on Twitter.

There is no denying this fact. We can see it as an amplification of patterns already identified by Thomas Frank in What’s the Matter with Kansas?

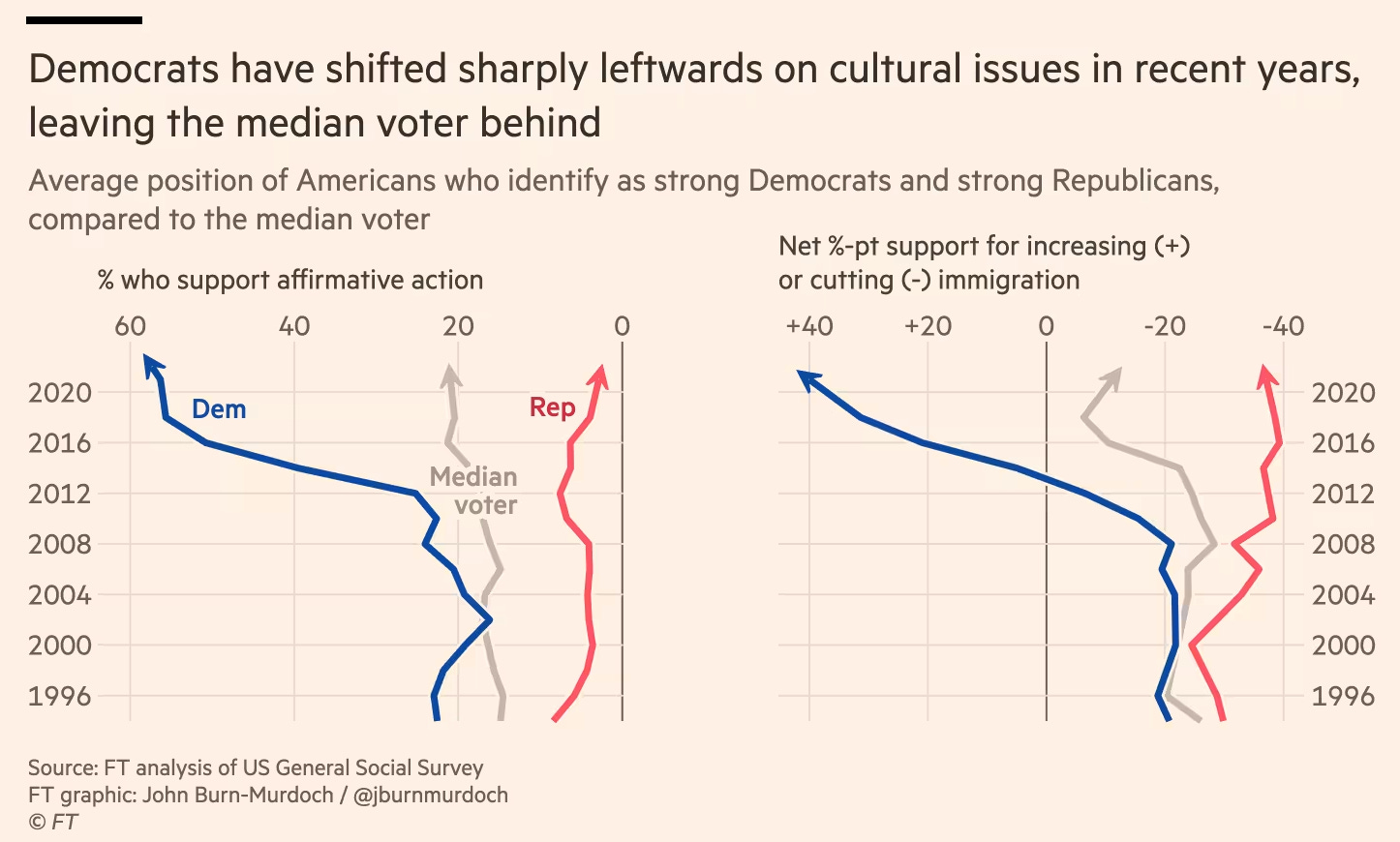

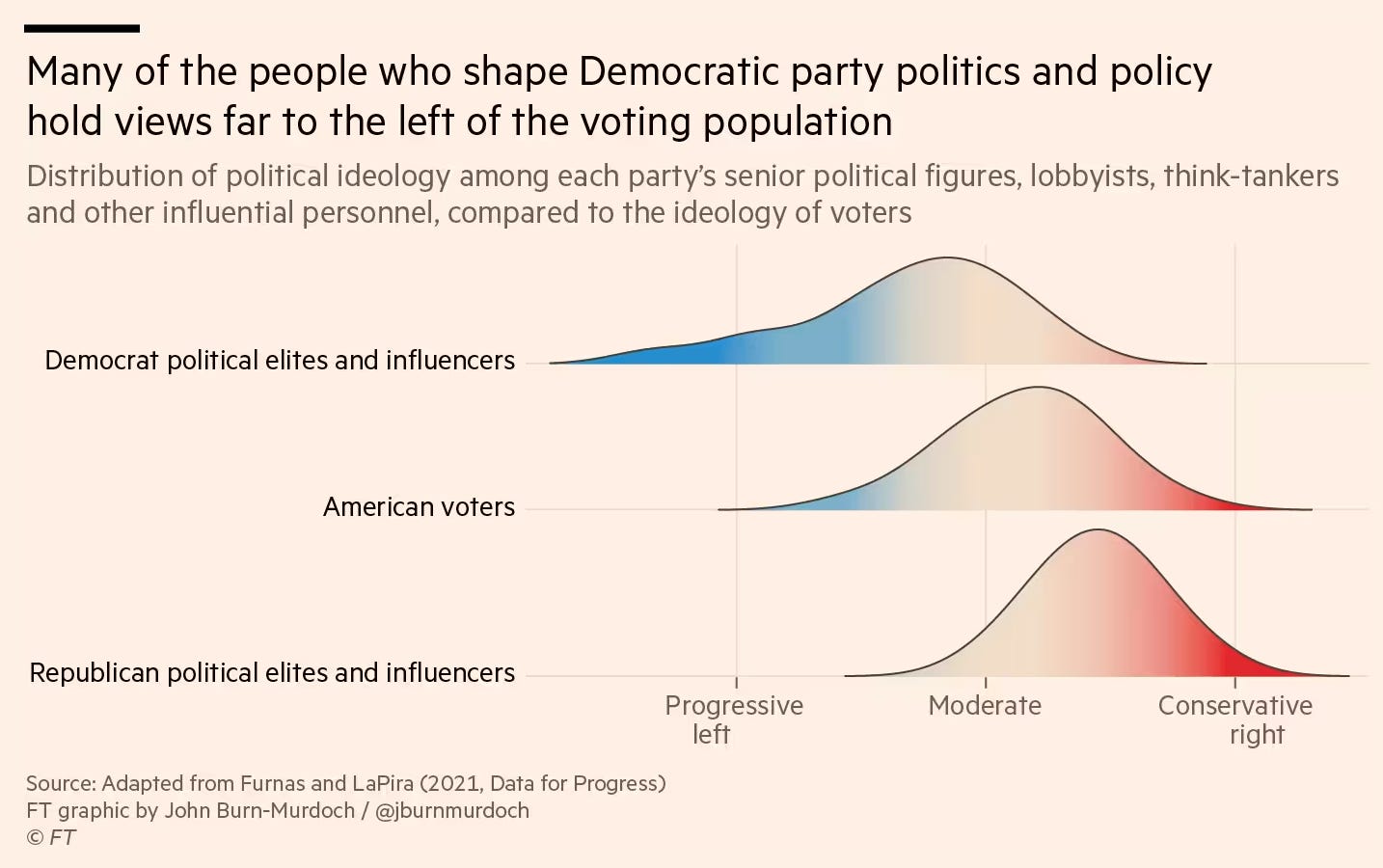

Democrat elites are now demonstrably far to the left of the median American voter on the Downsian left-right spectrum we have inherited from the late-19th century. This offers a straightforward explanation of why the left has been outmaneuvered by the right. The upshot for Democrat politicians, David Shor and Ruy Teixeira suggest, is that they must move closer to the median voter if they want to be more electorally successful.

Teixeira goes one step further in his structural analysis of the problem. The problem is not so much that Democrat elites and influencers are far to the left of the median American voter. Rather, the problem is the institutionalized agenda-setting power of progressive advocacy groups. The Groups, he says, should be thrown under the bus. After much huffing and puffing, even Ezra Klein, from his perch at the Grey Lady, bought the story.

These accounts, more aware of structure than the nakedly tactical Toozian reference frame but not offering any overarching theory of the phenomenon, can be described as middle range theories. Like their academic counterparts, they jettison grand theorizing for specific explanations grounded in empirical evidence.

I have great respect for middle-range theories: rigorous and disciplined by empirical evidence, they have proven to be extremely productive; particularly in comparison with grand theories. But is this the correct mode of analysis for our use case, as it were? Ie, whatever our a priori appreciation for middle-range theories, do they offer the correct diagnosis of American political instability?

There are reasons to suspect that they may not. It is not clear at all that the two-dimensional Downsian left-right spectrum is ‘good enough’ for our use case. In particular, it may not apply at all to extreme politics. How can one think, for instance, that Milei is closer to the median Argentine than his political competitors? Of course not. Everyone knows he’s an extremist. And that if why he is president!

This vivid counterexample may not be devastating to the Downsian framework in general, but it does suggest that the framework may be quite unreliable for the sort of extreme politics we now have. In particular, it is hard to sustain the case that Trump is closer to the median American voter than his political rivals. At any rate, it seems unlikely that Trump won twice because he is allegedly closer to the median voter.

Indeed, a good case can be made that the proximate psychological mechanism for Trumpism is instead rejection of the elite-dominated political system as a whole. Is there any one who does not agree that, above all, putting him in the White House is a way of showing the entire class of political elites the middle finger?

And if this is the case then perhaps it is not a matter of great import that Democrat elites are far from the median voter. Specifically, regardless of their policy positions, they may be at the receiving end of the working class revolt, because they are identified with American elites and their institutions.

If this line of reasoning is correct, then the way towards a more compelling and encompassing theory of American instability lies in chasing the causal roots of the breakdown of elite-mass relations. But elite-mass relations in the abstract cannot be considered in isolation. They must be seen in the context of the party system as the institutional context in which elite-mass relations are managed in modern societies.

As Huntington explained in Political Order in Changing Societies, the great historical purpose of modern mass political parties was to bring the masses into institutionalized politics. While broad political participation came earlier to America, a truly national mass party that institutionalized the participation of the working class in politics did not emerge until the 1930s. In this system, the Democratic Party was hegemonic and the GOP had to adapt to the new order of national political life. The hegemony of the Democratic Party in the midcentury system was based on the fact that it had brought the working class into national politics, and retained its allegiance for decades. It was indeed the party of the American working class.

The 1950s was the heyday of mass politics. From the 1960s onward, the mass basis of national politics began to came under increasing pressure. The pressure came from multiple directions. One was endogenous. Postwar Keynesian macroeconomic management was geared towards generating high employment rates and wage growth to underwrite the class compact. But this generated systematic pressure towards price instability, eventually leading the Great Inflation that in turned opened the door to Volcker’s technocratic counterrevolution and Reaganite attacks on labor power.

Another was somewhat exogenous. The rise of mass media not only created a instantaneous national public sphere that cannibalized local political attention, it also personalized national politics, turning national elections into contests of personal charisma. While FDR towered over contemporaries, he did so on the solid foundations of deep intermediation whereby provincial elites and working classes were organically connected to the national leadership in what is often described as machine politics. Already by JFK, we find the first instance in the West of a creature created almost entirely by national media attention and celebrity, as described vivedly by Boorstin in The Image (1962). But we have to wait until Clinton and Obama to see the full flowering of charismatic politics.

Yet another was the rise of technocratic political consulting. These professionals brought in techniques perfected in corporate marketing and brand management to the political system. Instead of relying on the idiosyncratic and possibly unrepresentative feedback from political constituents and their own political instincts, politicians came to rely on polls, focus-groups and professional advice to discipline messaging and positioning. It is for this structural reason that political discourse in America sounds so canned.

All three of these developments brought professional class experts into positions of power and authority in the core of the media-political system. In doing so, they pushed the lay and the low completely out of the room. Heavily credentialed central bankers would run the economy; graduates of the same prestige schools would set the national agenda and the narrative; campaign strategists would tell politicians what to say and how. The mass publics of midcentury were reduced to the status of spectators, as unelected professionals seized the reigns.

By the mid-1990s, the political parties had been hollowed out. Instead of intermediating between the hinterland and the metropolis, the parties became one way conversations. Elite-mass relations, in the context of the new party system, became public relations affairs. Voters and small donors were to be managed from a great height with modern techniques of mass suasion, later given way to the micro-targeting campaigns of the more recent era.

The historical processes that led to the decomposition of the parties were poorly understood and went largely unappreciated. In the imaginary of the elites, the new system simply reflected the modernization of the political system. If you want to run the economy competently, would you hire a Goldman Sachs CEO or an outsider? If you want to run a political campaign, would you hire that famed firm on K-Street or rely on your in-state political allies? If you’re to hire a new scribe at the New York Times, would you hire someone from Columbia or Ohio State?

The combined effect was the opening up of a vast social, intellectual and empathetic chasm between the hinterland and the metropolis; between flyover country and the zones of coastal affluence; and between the working classes and provincial elites on the one hand, and the national elites on the other. Reduced to sullen enforced silence and its culture ridiculed on national television (Honey Boo Boo), the working class began checking out of national life whose contours began to be set by a narrow stratum of prestige-schooled elites.

Anger began to grow not just because of the economic insults of the new hourglass economy that worked like the Lewisian model in monstrous reverse, pushing working class breadwinners either into dead end jobs or into a life of indolence and dependence. It began to grow, even more importantly, I believe, because of symbolic insults; because working class people were re-excluded from participation in national life in any meaningful way. For it is one thing to be an outsider, and quite another to be thrown out after having participated.

Working class breadwinners have increasingly soured on the Democrats over the past quarter century. In doing so, given the inherited structure of the US party system, they were souring on the political system as a whole. And when anti-systemic politics returned to the United States, it did so not by a takeover of the Democratic party, the traditional container of anti-systemic politics. Instead, it was the GOP that was ‘seized from below,’ as it were.

The reasons for this are not hard to fathom. The loss of elite control threatened both major parties. But the Democratic party, with its greater density of professional class elites, was able to contain and channel the energies released by the Bernie revolution, while the GOP, which was much further along the road to decomposition and with a much lower density of professional class elites, proved less able to resist conquest by Trump and his counter-elites.

McNamara brought civilians who claimed to have expertise in what was called ‘systems analysis’ into the Defense Department. The Whiz Kids would rationalize the bloated and creaky bureaucracies of the armed forces. Billions were saved. But while this passion for numbers did much to rationalize the preparations for war, when applied to war-making itself, it generated an escalating catastrophe that came to grief with the ugly spectacle of the botched American withdrawal from Vietnam. This was the diagnosis offered by Harry G. Summers Jr., who was tasked by the Army chief of staff to do a postmortem of America's failure in Vietnam.

To the really smart people who were put in charge of various cogs in the ‘modernized’ media-political system, the meta answer to any question was always the same: ask the experts; bring in the whiz kids; just show us the numbers—no need for deep introspection. This rise of the technocracy and its ensemble of analytical frames tempered many cycles endogenous to the mass political system—the central bankers did deliver macroeconomic stability; many policies were rationalized.

For the most part, questions susceptible to middle-range interrogation found satisfactory answers. But this mode of epistemology and knowledge-acquisition sidelined larger questions of political order, political morality and class relations. Questions not susceptible to the technocracy’s analytical arsenal were dismissed as philosophical, abstract or unanswerable. The possibility that what was being left unattended could be the source of systematic risk and instability was largely ignored.

Above all, the question of whether the modern media-political system, with its categorical exclusion of working class breadwinners, was legitimate at all was not even asked.

This brings us full circle to the off-hand comment with which I began this essay.

Why had no one noticed for twenty years that the working class was in such distress that it was committing slow-moving collective suicide?

This question can now receive an approximate answer. No one noticed because for anyone in a position to notice, ie, any member of the expert class, the despair of the working class was simply beyond their field of vision. They didn’t know anyone who’d overdosed on heroin. That sort of stuff was only supposed to happen in dangerous urban neighborhood or the badlands of Appalachia!

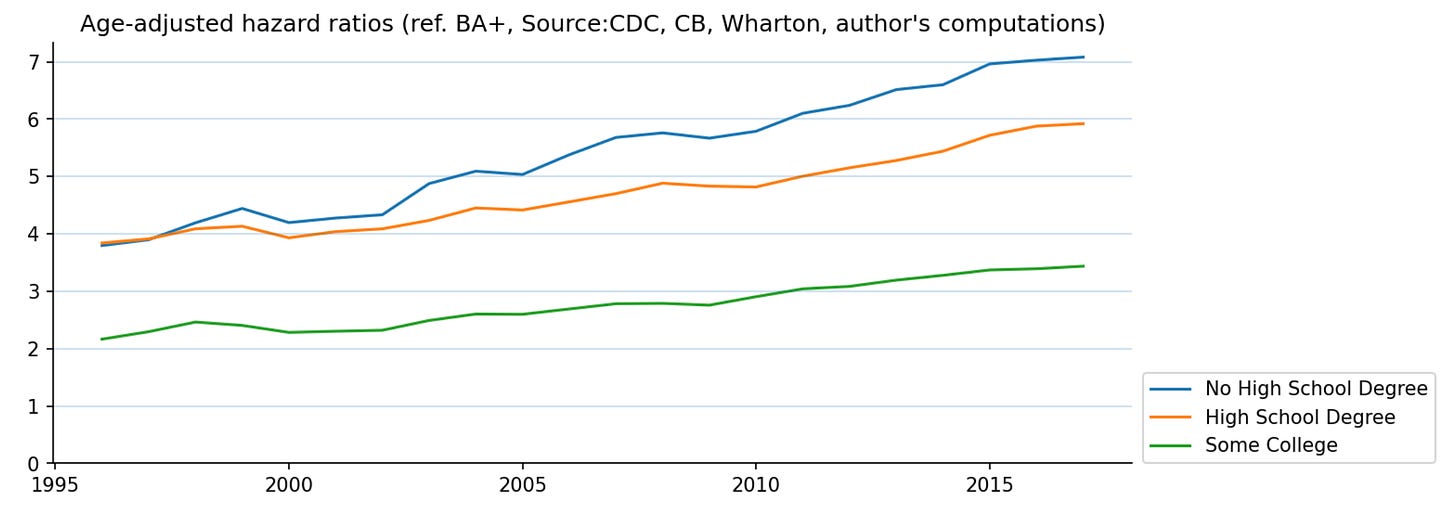

Even as late as last October, an observer as well-informed as Eric Levitz could not believe that high schools graduates were dying at higher and higher rates of alcohol poisoning, drug overdose and suicide. Not because there was any evidence to the contrary, but simply because the fact did not fit into the overall scheme of things. To wit, “The US is a rich country where most people are doing okay; except, of course, for the underclass, which has always plagued us.”

(When I showed that empirically, yes, high-schools graduates are dying of despair, did he believe it? Perhaps. I am sure he would’ve questioned the methodology had he not. But did it sink in? Did it shake his picture of the world? I doubt it. Our intellectual edifices are resilient things.)

This has been a long essay. In many ways, this is also a post-mortem of the Dems’ electoral humiliation. Stated plainly, the thesis that I have advocated here is this:

The Democrats lost in 2024 because we have a system that makes it possible for professional class to not even notice that the working class is killing itself in despair for twenty years.

This is why I do not believe the reference frames we use to diagnose these problems are up to the task. Projecting people onto policy space does not offer the sort of purchase people imagine. This was the context of my rude riposte to Jeer Heer.

My response may have been acerbic (and I have nothing against Jeet personally), but it felt right to me:

Bullshit. They don’t want elite determined policies that are better. They want to be fucking heard. They want to have a say. No system of elite policy making excluding actual grassroots representation of the working class is going to work.

I still think it is correct. What has gone wrong is not merely tactical choices, including the candidate for president, a la Tooze; what has gone wrong is not merely inefficient positioning in policy space, a la Shor; what has gone wrong is not merely the hypertrophy of the elite-advocacy complex, a la Teixeira. What has gone wrong cannot even be reduced to the economic insults to working class families; and even less to such any insults arising from import competition as our political elites claim to believe now. No, sir. What we have here is the wages of a media-political system that categorically excludes the working class from participation. And until this problem is recognized and fixed, there is going to be no progress at all. And the United States will remain mired in instability.

"The question is not only why the American working class family unraveled—even closer to the bone is why it took so long for anyone in the expert class to even notice."

Because the experts know that if they ask those questions, they may not like the answers they get.

So what happens is you get a Paul Krugman glibly explaining that inflation isn't really a problem, and producing very nice, very experty charts to demonstrate this quite convincingly, simply by taking out food, energy, housing and used cars (I mean, who uses any of those?) from the analysis, and voila! inflation isn't so bad!

Anyway, it is rich in Schadenfreude to watch liberals and democrats blame everyone and everything, everyone and everything but themselves and their policies.

"... for the same reason it took Case and Deaton 15 years to even notice that working-class Americans were killing themselves in despair."

Ditto the time it took Autor, Dorn, and Hanson to "discover"** the China shock: https://www.nber.org/papers/w21906

**discover translates as "make palatable to economists whose training is mainly math plus unspoken/unspeakable ideological premises"